Gender & Sexual Cyberviolence: An Exploratory Cross Cultural Inquiry

Editor's note: PBJ Learning is proud to provide a platform for Julian Siita's thesis on gender and sexual cyberviolence. It is a woefully understudied issue that is affecting everyone with access to the Internet. Please reach out to the author at [email protected]

WARNING: The reality is that the Internet is a dangerous place, and we would be doing you a disservice if we edited certain real-life, reality-based terms out of these materials. Be aware there are many terms in here that could be troubling, triggering, or “not suitable for youth,” so please use your discretion as you continue. There is quite honestly no way to prepare someone for a discussion about this topic without difficult terms, so be prepared.

SIITA Julian Saaka

DLMA

GENDER & SEXUAL CYBERVIOLENCE: AN EXPLORATORY CROSS CULTURAL INQUIRY

Thesis supervisor: Dr. Jose Alcaraz

« I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of personal work and that any direct or indirect reference to the work of third parties is expressly indicated. I remain solely responsible for the analyses and opinions expressed in this document, which are not representative of the views or position of ESDES »

Acknowledgements

Firstly I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Dr. Jose Alcaraz for constantly encouraging me throughout this process. It was a challenge and he cheered for me every step of the way.

Secondly, I would like to thank The Kahiigis, Mr. Kuruvilla, Dr. Zawedde and Aunt Vivian without whom this thesis would not be possible.

Lastly I would like to thank my parents, my mother Sarah Nantongo for her prayers and my late father James Saaka who would have been beaming throughout this.

SUMMARY

Part 1: Literature Review

1. Feminism

2. Patriarchy

3. Resistance

4. Conclusion

Part 2: Field study

1. Overview

2. Context of the study

3. Case study data

4. Data analysis

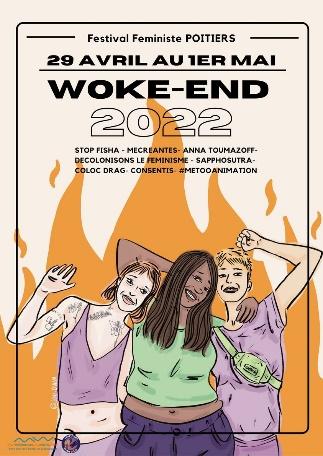

5. Presentation of results (Stop Fisha)

6. Presentation of results (WOUGNET)

Part 3: Discussion

Introduction

1. Association Stop Fisha

2. WOUGNET

List of acronyms and abbreviations

Term | Definition/ Full Version |

WOUGNET | Women of Uganda Network |

DDA | Digital Dating Abuse |

CVAWG | Cyber violence against women and girls |

Introduction

The increasing reach, aim and ever insinuating nature of the internet and its intricate web of technologies has made sure we are all more connected than ever. In the click of a button and the swipe of a finger, we can have a front row seat to each other's lives online. In fact, the 2020 coronavirus pandemic which grounded people and organisations' lives alike, the necessity of our presence online increased internet usage to 50% to 70% (Beech, 2020).

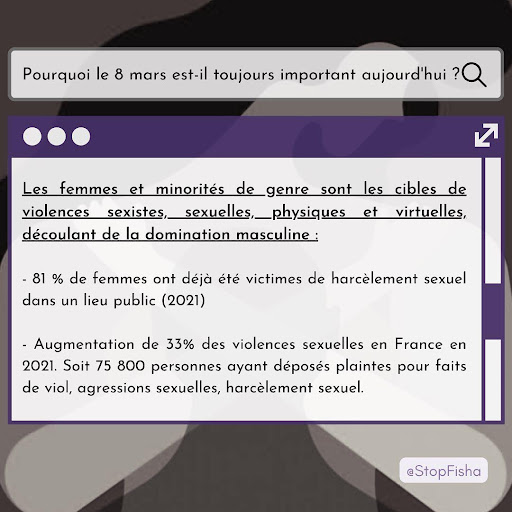

The (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014) found that 1 in 10 women has experienced cyber harassment since 15 so it is clear that cyber harassment is not a new problem. However, with increase of access comes increase in the occurrences of cyber harassment and cyberviolence. This threat of cyber violence looms over women's presence on the internet. In a study commissioned by the European Parliament, 15% of women said they had experienced some form of cyber harassment (Wilk, 2018).

(European Institute for Gender Equality, 2017) reports that women and girls are a particularly vulnerable demographic to the scourge of gender and sexual cyberviolence. One in three women will have experienced a form of violence in her lifetime, and it is further estimated that one in ten women have already experienced a form of cyber violence since the age of 15. However, some women and organisations are fighting back. This aim of this thesis is to examine the portrayal of gender and sexual cyber violence within the context of two organisations; a French non-profit organisation (Association Stop Fisha) and a Ugandan non-governmental organisation (WOUGNET) and to understand how cyberviolence is tackled by these organisation through their different activities. Through a thematic analysis of visual and written data collected from one organisation's social media accounts and book and interview transcripts with the employees of the other, I will explore the following questions:

1) How do the organisations portray gender and sexual cyberviolence?

2) What activities are they employing against gender and sexual cyberviolence?

To further this, an exploratory examination was conducted by interview into a similar non- governmental organisation in the Global South known as Women of Uganda Network, to compare and contrast the similarities and differences in both the portrayal and fight against gender and sexual cyberviolence. (Thomas and Davies, 2005) mentioned that debates within feminist theory around the subject of resistance and when it was seen to count have led to the emergence of a more nuanced and varied conception of resistance. In this way, the organisations' activities can be seen through the lens of resistance against cyberviolence. In another context, women's attitudes and actions in the workplace have been shown as made up of nuanced commitments and resistances to context-relevant identity issues. Therefore, they are not entirely individual and private nor entirely collective and public (Aldossari and Calvard, 2021). Both of these lead to an understanding that resistance does not have to be overt to count and can be more subtle.

To understand the context of gender and sexual cyberviolence, a literature review was conducted on the definition and history of feminism, with a breakdown on the different waves of feminism. Following this, an exploration of feminist theory in relation to patriarchy, sexual violence and resistance was conducted along with an evaluation of past studies of cyberviolence. For this thesis, the focus was to gain an understanding of the how two different organisations (one in the European context and the other in the Global South) portrayed cyberviolence and their activities to combat it in relation to resistance.

Part 1: Literature Review

1. Feminism

There is no one definition of the word feminism because it has evolved according to what was being resisted against. Indeed in (Thomas and Davies, 2005) it is quoted from (Weedon, 1987:1) that the word feminism denotes a politics that is synonymous with causing trouble, critique and change. (Ward et al., 1999) also states that feminism is a troublesome term that encourages people to express opinions, however it can be unclear what is being talked about, due to limited knowledge or prejudiced misrepresentations.

1.1 Introduction

The problem then, according to (Ward et al., 1999) remains that feminism, despite its diversity in discussions had its centre often rooted in the single entity of equality. (Ward et al., 1999) continues to note that because there have always been differing approaches, those wishing to gain a handle of its meanings came face to face with obstacles in understanding it.

For our study, it serves as a broad starting point in which to consider the concept of gender and sexual cyber violence.

1.1.1 The First Wave of Feminism

This period featured Mary Astell who was considered one of the earliest true feminists, as she was the first English writer to explore and assert ideas about women which are still recognisable today. Though she was conservative, she advocated for the women's freedom from the conventions of the time (such as marriage) that resulted in underdeveloped and untrained minds. Her negativity toward men and marriage did not endear her to many women readers(Walters, 2005).

(Walters, 2005) added that Astell's argument was that women were just as capable as men in spite of a lack of training to cultivate and improve them. She was a big supporter of other women and encouraged women to take their lives and selves seriously. This came through trusting their own judgement and choosing their own way in life whether that meant education or other means of development.

Another key figure cited by (Walters, 2005) was Mary Wollstonecraft, who argued for women to be given the chance to enhance their intelligence. She argued that femininity was a class based construct with artificial foundations. The fact that girls learned to be women when they were barely out of diapers, an exploitation of this femininity was their only option. To remedy this she proposed better education for girls, and a novel departure for her time: universal education, until at least 9 years old.

1.1.2 The Early 19th Century

(Walters, 2005) states that although William Thompson and John Stuart Mill penned two of the best-known 19th-century arguments for women's rights, the authors both made sure to acknowledge their wives who actually inspired their ideas.

(Walters, 2005) mentions John Stuart Mill's 1869 publication The Subjection of Women, as a key examination into why treating women as less than was wrong and a death sentence to the improvement of human beings. She further mentioned that he was influenced by his wife Harriet Taylor, who was already married with 2 small sons when they met in 1830. They would eventually marry in 1851, 2 years after the death of her husband and a friendship of almost twenty years between them.

William Thompson's views on marriage were expressed in his book addressed to and inspired by Anna Wheeler. She had become known for her reform movement interest upon her return to London two years after the death of her husband. In her case, she left her husband who was a drunkard. Thompson's book delved into the married woman's plight as being only viewed as the property and pliant servant of the man she is married to (Walters, 2005). It referred to her home as a “prison house” emphasising that everything in it including his breeding machine, the wife belonged to him. It likened married women's situation to that of slaves located in the West Indies(Walters, 2005).

At this time, mothers did not have rights over their children and family property, instead being treated like a servant. Despite the modern feminist criticisms that these writings focused only on married women and no single women or daughters, the vulnerability of married women having no legal existence in this period was dangerous(Walters, 2005).

(Walters, 2005) states that by the mid-19th century, other women like Frances Power Cobbe were taking up the fight for better education and the issues faced by both single and married women. Cobbe spoke about the women in miserable marriages and campaigned for a Married Woman's Property Act.

(Walters, 2005) adds that across the pond in America, the feminism movement was borne out of the anti-slavery movement which began to take root in about 1830 despite some of these groups being whites only. She mentions a key figure, Sojourner Truth who was a former slave that rejected the idea that women needed men's protection and spoke out against the right to vote being awarded to former male slaves who were freed post-Civil War. Women were granted the right to vote in 1920 and all black people in 1970.

The key issues at this time were the legal existence of married women in relation to property and their children and the right to vote.

1.1.3 The Late 19th Century

In the late 19th Century, a more defined women's movement began to emerge in England around issues such as women's need for better education and increased options for employment. This was initiated through campaigns organised by Barbara Leigh Smith and a group of her friends who came together as a reaction against the fact that a Victorian woman's highest virtue seemed to be constrained by a narrow definition of femininity(Walters, 2005). Women were generally expected to be passive and a woman born into the middle class maybe had the chance to earn a terrible living with few other options available.

If a woman was unhappily married there was no way out and despite some women having impressive achievements, they still shied away from speaking about the emerging feminism of the period. The Contagious Diseases Acts which was a significant campaign, sparked a wider conversation about women's rights and autonomy over their own bodies because it created dissent, thus shedding light on the need for equal treatment and the recognition of women's agency in matters of sexuality (Walters, 2005).

It was stated by (Walters, 2005) that this campaign not only shed light on the cruel and hypocritical double sexual standard of society but also had far-reaching implications. The first of these Acts was passed in 1864, granting the police the power to apprehend any woman suspected of engaging in prostitution in certain ports and garrison towns. These women would then be subjected to invasive internal examinations, often using brutal methods, and if found to have any signs of venereal disease, they would be confined to hospitals. Subsequent extensions to the Act were made in 1866 and 1869.

(Walters, 2005) mentions that as the implications and injustices of these Acts became apparent, women began to voice their opposition with notable figures such as Elizabeth Garrett, Florence Nightingale, and Harriet Martineau joining the protest and arguing against the regulation system that targeted women. The campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts exposed the deep-rooted inequalities and injustices within society, particularly in regards to sexuality and gender. It challenged the prevailing notion of a double standard, whereby men engaging in prostitution were not subjected to the same scrutiny and punishment as women.

(Walters, 2005) reports that in 1869, a Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act was set up becoming the first group of respectable women to be able to effectively apply pressure. First, they started on the brutal laws against prostitutes or those suspected of prostitution and then later as the right to vote became more important. Not only was it seen as symbolical recognition of full citizenship but it was also the most practical way to effect changes and push forward reforms.

(Walters, 2005) describes this campaign for the right to vote as the Women's Suffrage Movement which would eventually lead to success in the United States in 1919. She adds that in other countries like New Zealand and Australia, women were granted the right to vote in the 1890s, with participation in Federal Elections being granted in 1902. Denmark granted this right in 1915, and the Netherlands in 1919.

Key fights here were still advancement of women's education and the right to vote.

1.1.4 Early 20th century Feminism

(Walters, 2005) mentions that after English women achieved legal and civil equality, the movement was divided on whether the next fight should be for the same terms of equality as men or to focus on women's other needs and problems.

In addition, because the effects of the First World War provided women with the chance to work outside the home with over a million women working in munition factories, engineering, hospital, this brought forth the demand for pay rises and equal pay to that of men (Walters, 2005). However, due to the war a lot of women became widows or remained unmarried.

1.1.5 Second Wave Feminism

Post Second World War brought about what is sometimes referred to as ‘second-wave' feminism in multiple countries. This was marked by the United Nations established a Commission on the Status of Women and then issued a Declaration of Human Rights two years later, which confirmed men and women's equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution as well as women having a right to special care and assistance in their role as mothers (Walters, 2005).

In fact, (Walters, 2005) further reports that feminism was acknowledged by the UN during three international conferences on women's issues in Mexico City, Copenhagen and Nairobi between 1975 and 1985, with it being noted that the differences in women from different from different regions, classes, nationalities, and ethnic backgrounds. It became clear that different women had various concerns and killed the myth of sisterhood that assumed all women shared identical interests.

It was also during this wave that more Western women continued to write on the topic, a notable one being Simone de Beauvoir whose writings explored a woman's experience. Beauvoir explored the concept of male activity being considered more valuable and important than Nature and Woman. In addition, (Walters, 2005) she stated that women had never been considered fully human, having been denied the right to create and find meaning in projects outside of their role in relation to the man. She identified this as being “Other” and seen as an object by and for men. So many different women identified with this especially in noting the similarities in personal frustrations towards the general conditions of women.

This movement also brought to the forefront issues of intersection between race and feminism through the writings of people such as Bell Hooks in her Feminist Theory: From Margin to Centre (1984), which stated that the feminism of the time was racist and that the women who were the most victimized by sexist oppression were not allowed to speak out. It called to attention those who had been disillusioned.

Another notable issue during this period was a woman's right over her own body. Because a woman's looks and appearance was consistently correlated to her value, this issue seemed minor at first. It was and still is consistently reinforced through images in the media that show us an unattainable standard of beauty to aspire to, a standard that even the people in those pictures do not meet themselves. Western Feminists were concerned by how these images caused a desperate chase after the latest fashions leading some to resort to even more dangerous methods such as dieting (through anorexia, bulimia and restrictive eating) or even continuous self-mutilation through plastic surgery (Walters, 2005).

1.2 Beyond Western Feminism

From the paragraphs above, it is clear that there has never been just one issue plaguing women. Whether it is the advancement of education, property rights, the right to vote or equality and anti-discrimination, feminism has come a long way and will exist for as long as world shifts create more issues and inequalities. It is important to note that while Western Feminism receives majority coverage, women in other parts of the world deemed less important or less developed have also had to contend with similar if not harder problems. These problems have been exacerbated by beliefs of their ethnic groups, caste, and religion often being complicated by a struggle for an establishment of democratic government and for more basic freedoms (Walters, 2005). In places such as Latin America, Africa and Asia and the Middle East, where generations of women's lives have been affected by colonialism and neo-colonialism, feminism takes on a different flavour and the struggles are often different than what has been expounded upon in the historical overview above. When we bring the focus to Africa, local beliefs have also about practices out of differences in class, religion, ethnic origins and all following behind the legacies colonialism left behind.

A brilliant penning by (Ebila and Uhde, 2020) recognizes the lack of opportunities for mutual discussions to occur between Africana and European feminist researchers as well as not enough open access to publish in. In addition, they mention that the information available on the lives of women in Eastern Africa is all over the place and often overshadowed by poverty as the issue at the forefront. by scholars and activists and from the critical media. However, we felt that there have. It is therefore even more important to recognise the marked differences in Western feminist movements and African feminist movements. Though research on feminism and gender in Eastern Africa has been going on for over three decades, access to research reports and literature is difficult although places like the School of Women and Gender Studies (founded in 1991) at Makerere University in Uganda are working to overcome this.

(Ebila and Uhde, 2020) gave a succinct summary of what African feminism involves, stating that it is varied and includes issues of mothering, gender relations, sisterhood, land ownership, farming, trade, peacekeeping, education, and how all these build the lives of girls and women in relation to the men in their lives to make life better for all. Quoting (Mikell, 1997) who stated that African feminism is not just about the political participation and leadership but everything – the bread, the butter, and power, and about how these things impact the lives of African women. (Ebila and Uhde, 2020) further clarify that the work of women in Eastern Africa not only contributes to improvement of living conditions but to the development of their immediate families and societies. By contrast (Goredema, 2010) states that African feminism concerns itself not only with the rights of women from Africa but is also inclusive of those living in the Diaspora as many of the contributors to the literature have often lived “abroad”. It is therefore limiting to let geographical location be a deciding factor as the name would imply. Instead we must understand that the debates, practices and implementation of African feminism are mostly pursued on the African continent. This means that despite difference in location (East, West, North and Southern parts of Africa), women all over Africa and within the diaspora cannot separate from the challenges (individually and collectively) against patriarchy, oppression and underdevelopment.

2. Patriarchy

(Napikoski, 2021) defines a patriarchy, through its origin from the ancient Greek patriarchs, as being a society where power was held by and passed down through the elder males. She adds that the description of a “patriarchal society,” is closely connected in that it reiterates the idea of males holding power and privilege: head of the family unit, leaders of social groups, boss in the workplace, and heads of government.

(Ortner, 2022) defines patriarchy as a social formation of male-gendered power with a particular structure that can be found with striking regularity in many different arenas of social life, from small-scale contexts like the family, kin groups, and gangs, up through larger institutional contexts like the police, the military, organized religion, the state, and more.

As it is ingrained in our society, we know that women have not been able to divorce themselves from experiencing its effects or even being influenced by it in a multitude of ways.

2.1.1 Patriarchy's influence on women

According to (Dickerson, 2013), living in a patriarchal culture provides men with certain privileges and entitlements that are not available to women including access to ways of being and performing that are closed to women. In addition, this same patriarchy influences women to respond in defined ways, often accommodating and deferring to male interests (Hare-Mustin & Marecek, 1988, 1990; Hare-Mustin, 2004; see also Coontz, 2012 as seen in Dickerson, 2013).

In understanding this, she continues by noting feminism shines a direct light on the effects of a patriarchal culture on women's lives and continues to critique male privilege. In the patriarchal structure, (Ortner, 2022) states that the women (and “wrong” kind of men) remain outsiders regardless of if they come “inside” without protection and sponsorship from those who are considered first class. In this way, they remain as a type of second class citizen (with lower pay, for example), and are as a result subject to endless harassment, up to and including rape.

(Ortner, 2022) mentioned the fight against second class citizenship was the focus of earlier feminist movements and feminists began to later understand that entrance into the “club” and reaping its benefits was not the only part of it. They ultimately needed to dedicate their focus to breaking up and disrupting the structure in place, the social organization of patriarchal power.

(Ortner, 2022) concludes that wherever patriarchy resides, the assumption is that its members, are all “superior men” or potential superior men, and which in turn excludes not only women but other men in those other categories who fail to meet this test. For the study, this point is important because men regardless of whether they are considered superior or not, ultimately use violence as a way to subjugate women.

2.1.2 Violence

Violence is defined by the World Health Organization as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal development, or deprivation.”(WHO, 2002 as cited in Lokaneeta, 2016).

However, (Lokaneeta, 2016) states that this definition does not draw enough attention to the victims, perpetrators or the reasons behind the harm; rather it only captures the scope of harm associated with violence. In addition, this definition is not specific enough to accurately capture the nature of gender and sexual cyber violence.

It is thus important to understand that violence does not happen in a vacuum. (Lokaneeta, 2016) states that feminist scholars have sought to differentiate between the many forms of violence including that they exist on a continuum while keeping them framed in their specific context.

Through their studies, feminist scholars have examined the different roles states, non-state parties from dominant classes and communities and individual offenders have played in the endorsement of violence (Lokaneeta, 2016). The author continued by noting the existence of structural violence (suffering induced by economic and political forces, such as extreme poverty, unjust healthcare policy, slum demolition); representational and symbolic violence (discursive constructions that dehumanize and objectify some humans, while celebrating the “natural superiority” of others), and epistemic violence (forms of knowledge production that deny or undermine the agency and subjectivity of particular populations).

Scholars have also investigated and documented forms of racialized and gendered violence ignored in mainstream approaches, and developed path breaking works that address racialized violence (e.g., Middle Passage, branding, slave plantation, lynching, prison industrial complex) and gendered violence (e.g. rape, kidnapping, domestic violence, sexual harassment, feminization, forced sterilization). For this study, the focus will remain on violence directed towards women and girls.

2.1.3 Sexual violence

Sexual violence is a term that is defined as follows:

“Any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic … against a person's sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work.” (WHO, 2002, p.149 as cited in Powell and Henry, 2017, p.4)

It works as a more inclusive definition because it covers both physical acts e.g. rape and sexual assault but also offenses where there may not be any contact e.g. non-contact offenses and behaviours, such as sexual harassment and sexual coercion (Powell and Henry, 2017). In addition, the authors state that its widespread usage among academics, professionals and victim-survivors, shows that violence as not simply a physical act involving physical injury but also a psychosocial and structural problem.

Knowing that sexual violence is a structural problem, sexual violence cannot be referred to without acknowledging the long held debate by feminist scholars and commentators (Powell and Henry, 2017) over the existence of a rape culture, with some arguing that a rape culture is one that implicitly and explicitly condones, excuses, tolerates, normalises and fetishizes sexual violence against women).

This is important as it leads into the term ‘technology-facilitated sexual violence', a term used to encompass a diverse range of acts involving technology, drawing on the WHO definition (Powell and Henry, 2017). This term, though it will not be used through the thesis, encapsulates the context of gender and sexual cyber violence which is what the thesis will entail.

2.1.4 Women's experiences of sexual violence

(Powell and Henry, 2017) note that sexual violence (and gendered violence more broadly) is both a private and public harm because of the shame and taboo around being a victim of sexual violence. This means that an individual who has had this personal and private violation, most often perpetrated by a known man in a private, residential location is reluctant to report informally to family and friends or formally to the police. It adds to the silencing around the issue and the entitlement of husbands in various countries to their wives' bodies.

Women grow up being socialised to bear ‘everyday' intrusions, routine sexual harassment and sexual assaults in public spaces, with a much deeper fear than men of interpersonal violence in public space thus having to engage in behaviour to safely manage these situations during their day. Thus women's private and individual experiences of sexual violence also shape women's public and collective experiences of moving through a society in which their safety, and particularly their sexual autonomy, is uncertain (Powell and Henry, 2017).

It poses the question as to how this shows up in instances of cyberviolence, which occurs online, a place that can be considered another extension of the public domain.

2.1.5 Cyber violence

(Backe et al., 2018) report that the term cyberviolence emerged in the early 2000s, with the widespread diffusion of portable laptops and Web 2.0, with its meaning remaining highly contested and steeped in controversy (Grant 2016; Jeong 2015; Lenhart et al. 2016).

Broadly speaking, the concept of cyberviolence is meant to encapsulate the kinds of harm and abuse facilitated by and perpetrated through digital and technological means. The UN's adoption of the term in their 2015 Cyber Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) report brought about debate about the definition of cyber VAWG, because of its terminological overlaps with other forms of violence and crime, and the extent to which the term's attempt to capture all forms of online violence was either accurate or fair (Chisholm, 2006).

In their review, (Backe et al., 2018) held that there was a lack of consistent, standard definitions or methodologies used to conceptualize and measure cyberviolence. Most of the literature focuses on cyberbullying among heterosexual adolescents in high-income countries. Demographic data on perpetrators are limited, prevalence estimates are inconsistent, and almost no primary research has been conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Cyberviolence is not only associated with negative psychological, social, and reproductive health outcomes but also it is linked with offline violence, disproportionately affecting women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities. There is an urgent need to develop a uniform set of tools to examine cyberviolence internationally. Future research should explore the gendered dimensions of cyberviolence and the continuum between online and offline violence, including in LMICs. (Backe et al., 2018) suggest that the various terminologies used to describe cyberviolence are similar but not necessarily interchangeable (IGF 2016), demonstrating a lack of consensus within the research community on how to define and categorize these digitally based behaviors and actions. The result is an intermeshing of categories following which they created a table showing the breaking down of the different forms of cyberviolence as shown on the next page.

Table 1. Cyberviolence Tactics

Tactic | Definition |

Defamation | the false statement of fact often used to damage the reputation of someone; can include slander or libel |

Doxing (sometimes spelled doxxing) | releasing identifiable, and often private, information about an individual online; can include name, phone number, email address, home address, etc. and result in in-person stalking or harassment, sometimes physical violence or threats |

Flaming | when a victim is belittled or demeaned on a live public forum (Pittaro 2011) |

Hacking | gaining access to someone's private computer or data stored via digital means, such as Cloud or other storage architecture |

Happy slapping | recording or filming an attack on a mobile phone |

Impersonation | creating an account using the name or the domain name of another person, often with the intent to harm, harass, intimidate, or threaten others |

Sexting | sending of sexually explicit messages or images by cell phone (Drouin et al. 2015), could be coercive in instances of intimate partner aggression |

Surveilance | using GPS to track the movements of someone via their phone or other wireless device; secretly monitoring texts, phone calls, emails, messages, etc. conducted on someone's personal accounts |

Trolling | trolls often commit intentionally inflammatory and divisive speech online (Mantilla 2015; Phillips 2015) |

Source: Backe et al., 2018, p. 137.

Table 1, shows a starting point from which to understand the portrayal of gender and sexual cyberviolence. Through reference the tactics that perpetrators can use to enact the different types of gender and sexual cyberviolence, an understanding of the vast landscape of the different types of gender and sexual cyberviolence. However, it may does not paint a complete picture of the new types that may crop up with the advancement of the technological landscape which may encompass several of the tactics shown.

In addition to this, (Backe et al., 2018) notes the variation and interchangeability of terms that are used in relation to cyberviolence as shown in the table below:

Table 2. Cyberviolence Concepts and Related Terminology

Cyberviolence term | Related terminology |

Cyberviolence | Online violence, digital violence, digital abuse, CVAWG, cyber abuse, cyber aggression, technology-related violence |

Online harassment | Electronic harassment, Internet harassment, cyber gender harassment, cyber/online sexual harassment, technology-related/CVAWG |

Cyberbullying | electronic bullying, Internet bullying, cyber aggression, online bullying |

CDA | cyber dating violence, electronic teen dating violence, online dating abuse, Internet partner cyber aggression, cyber teasing, DDA, electronic leashing |

Revenge porn | cyber rape, non-consensual pornography, involuntary porn, image-based sexual abuse |

Source: Backe et al., 2018, p. 137

From Table 2, it is clear that there is no one uniform term to which cyberviolence can be attributed. However, there is no inclusion of gender and sexual cyberviolence. The closest term is technology related cyberviolence which is similar to technology-facilitated sexual violence that was referenced in 2.1.3 above. Therefore it follows that with no set uniformity of terms, it will be sufficient to use the term gender and sexual cyberviolence throughout the study in reference to the different terms of technology facilitated/ related cyberviolence that will be explored.

3. Resistance

Without resistance, there would not be feminism. It was one of the most effective tools that the different movements throughout the years employed whether in subtle ways or in a more overt manner. Therefore, it is an important element of the literature review.

3.1.1 Resisting violence

When dealing with violence of any kind, an important piece of the discussion in the context of feminist studies is the resistance to it. This may take any form from political to the creation of forums to consider alternatives to violence, or the development of mechanisms to negotiate everyday life in a way that mediates the effects of such violence (Lokaneeta, 2016). As violence or the threat thereof has always been used to subdue different minority and disadvantaged groups, it gives an important backdrop through which to consider the question of how the different organisations portray the gender and sexual cyberviolence and the activities they do to offset this new form of violence.

3.1.2 Feminist theory and resistance

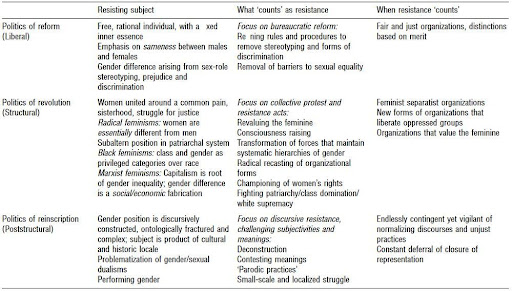

(Thomas and Davies, 2005) mentioned that the debates within feminist theory around the subject of resistance and when it was seen to count led to the emergence of a more nuanced and varied conception of resistance. However, before we get into these different definitions, (Thomas and Davies, 2005) provides a three way framework through which to view the feminist theory-resistance-organizational relationship as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Three-way framing of the feminist theory—resistance–organization relationship

Source: Thomas and Davies, 2005, p. 715.

The authors followed up by highlighting the different definitions of resistance according to the different feminist perspectives as shown in the framework, most notably with this quote showcasing the Foucauldian feminist framework which took a micro- political understanding of the term resistance:

“Resistance to the dominant at the level of the individual subject is the first stage in the production of alternative forms of knowledge or where such alternatives already exist, of winning individuals over to these discourses and gradually increasing their social power.” (Weedon, 1999, p. 111 as cited in Thomas and Davies, 2005).

Within the structural approach, the authors stated resistance counts most notably with women speaking out and universally identifying other women's shared experiences. It was often defined as the construction of theory on women, for women by women. Therefore (Thomas and Davies, 2005) concluded that empowerment against resistance in this instance took shape by making the forms of oppression more visible and engaging in activities of consciousness-raising in order to turn an advantage for femaleness. The downside was that it was prone to silencing the voices of multidiverse participants.

By contrast, for Marxist feminists, gender difference is a social or economic struggle, and therefore not related to gender because they considered there to be no real differences between men and women. Radical feminists, on the other hand, were viewed as the source of resistance but with the view that the common oppression standpoint allowed women the distinctly advantageous viewpoint to expose the reality of gender subordination and to go beneath the surface of appearances (Hartsock, 1983 as cited in Thomas and Davies, 2005).

One of the important takeaways of the (Thomas and Davies, 2005) study was the explicit recognition that resistance within organization studies was mainly derived from studies on blue-collar workers, so subsequently there was a tendency to associate resistance with activities amongst this category of worker. Despite there being existing studies exploring professional and managerial resistance e.g. (Raelin, 1991; LaNuez and Jermier, 1994; Knights and Murray, 1995), in general managers and professionals were not usually considered because they do not traditionally fall under the categorization of oppressed.

Another was when (Thomas and Davies, 2005) stated that organization studies were increasingly discussing the shift of understanding resistance from more than just collective, overt activities to more subtle, every day, low-level forms of struggle and challenge. (Thomas and Davies, 2005) mentioned that the debates within feminist theory around the subject of resistance and when it was seen to count led to the emergence of a more nuanced and varied conception of resistance.

Thus the (Thomas and Davies, 2005) study was important for showcasing resistance in a group not traditionally focused on before i.e. social workers.

4. Conclusion

Before getting into the thesis topic, a review of the main concepts and definitions was important for an understanding of the importance of the topic and its origins. Before we understand gender and sexual cyberviolence, we must understand the roots of violence and sexual violence. Before we understand violence and sexual violence we must understand the fact that they are in fact tools of the patriarchy. Before we understand the patriarchy, we must understand feminism and its origins, by going through a different overview of the difference in rights women found themselves striving for overtime.

From reviewing the different sources, it is clear that although the definition of cyberviolence has been studied before, those studies were limited to mostly Western perspectives (United States, Canada, and United Kingdom) on the topic. The research featured in this review is limited in that it only shows the definitions of cyberviolence in the United States, Canada and Australia with no features from other countries located in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In addition, (Backe et al., 2018) added that the primary research conducted has had a youthful focus in regards to its samples and these may not be a good representation of the general population.

My study will introduce commentary of a new developed country not previously included in the aforementioned review and studies as well as and an organisation from a lower to middle income country (LMIC) in the Global South. This is important because the empirical data on cyberviolence in African countries is limited. It which will shed a comparative light on how two different organisations in Uganda and France portray gender and sexual cyberviolence differently (through their activities and approach) with a context of resistance. This will be examined in the context of the organisations' activities.

Through a thematic analysis, this thesis will show how two similar organisations that work to curb the same issue (gender and sexual cyberviolence). However it is important to note that this is only an introductory inquiry into the organisational perspective in two different countries.

Part 2: Field study

1. Overview

The first part of this section will consider the purpose of the case study and research questions, examine its context with reasons for selection of the case. Next, an in-depth narrative of the data collection in order to provide a closer look at the case and methods chosen. This will be followed by details of the data analysis, ethical considerations of the methodology and finally what changes and reflections occurred throughout the case study.

1.1 Qualitative research methods (case study):

From the form of the research questions, the aim of the research was to compare how two different organisations (Association Stop Fisha and WOUGNET) portray gender and sexual cyber violence including the activities they carry out against it and how they portray resistance through these. Gender and sexual cyber violence and resistance are phenomena that would be difficult to quantify simply because they constitute the diversity of the human experience. (Tenny et al., 2022) states that such behaviours and attitudes, which can be difficult to quantify and capture quantitatively are thus better suited to qualitative research. The research takes on a descriptive nature because ultimately the research paints a picture of how Association Stop Fisha shows gender and sexual cyber violence and resistance on social media and in their book.

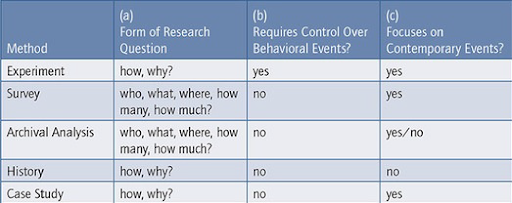

In addition, as my research questions were more open ended, making the decision to conduct qualitative research was straightforward (Tenny et al., 2022) and further supported by the considerations in Table 4. It acted as a guiding light in deciding which method to undertake. The decision to conduct a cross-cultural study of Association Stop Fisha and WOUGNET arose from the expectation that the answers to the research questions would not easily be put into numbers (Tenny et al., 2022). Instead it would feature perceptions of the data I collected analysed from social media, book and an interview. Then finally conduct a recognition of themes and patterns which would then be collated into discussions towards the answers.

Table 4. Relevant Situations for Different Research Methods

Source: Yin, 2018, p.39

Further pursuant to Table 4, because the research questions were explanatory (featuring “how”), they were more likely to lead to a case study (Yin, 2018). With regards to control over behavioural events, (Yin, 2018) posits that case studies rely heavily on two sources of evidence namely direct observation of the events being studied and interviews of the persons still involved in the events.

In addition to data collected from social media and a book, the case study will include an interview of an employee from the organisation based in Uganda (WOUGNET). I decided on a shorter case study interview which meant the interview took place over one sitting. According to (Yin, 2018), to these types of interviews may remain open ended and take on a conversational manner but follow the interview guide. Therefore, the interview was semi-structured in that it resembled more of a guided conversation rather than a heavily structured query. I prepared 4-6 key guiding questions as shown in Appendix A in order to guide the interviewee in their answer, however I allowed them to add/elaborate to their answer as much as possible in order to gain richer detail for my discussion.

2. Context of the study

First we need to understand the organisations selected for the case study, from their background and how they started, including what they do now in fighting gender and sexual cyberviolence.

2.1 Description of Association Stop Fisha

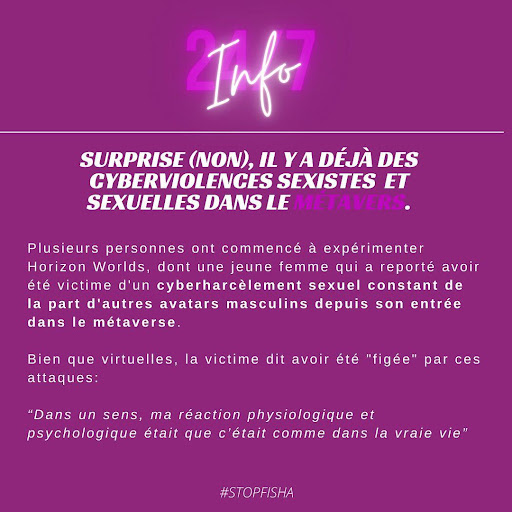

Association Stop Fisha is an activist collective in France that is made up of 92 students, high school girls, lawyers and employees who have gathered together to fight against gender based and sexual cyber violence in particular the ‘fisha' accounts that exploded in number during the 2020 COVID lockdown. The main hashtag associated with this collective is #StopFisha.

From just a few members to now hundreds of volunteers from all over France, the group continues to raise the alarm about the patriarchy and its resulting violence; whether it is on the street or online. Their commitment is proof of a system failure and the result of an emerging problem; cyber sexism and cyber violence and the resulting sexual and gender bias.

One of the most important things that made Association Stop Fisha stand out was that their inception was during the time of the 2020 COVID lockdown and within two months of existing they had managed to unite more than 12,000 active members ready to help (Stop Fisha, 2023)

Their method of fighting against cyberviolence takes a four pronged approach: the monitoring and reporting of online gender-based violence (track and report fisha accounts), legal and psychological support for victims, raising awareness and finally, advocacy.

2.2 Description of Women of Uganda Network

Woman of Uganda Network (henceforth known as WOUGNET) is a non-governmental organisation that was started in May 2000 by several women's organisations in Uganda to develop the use of information and communication technologies (henceforth known as ICTs) among women as tools to share information and address issues collectively. As an organisation, their vision is an inclusive and just society where women and girls are enabled to use ICTs for sustainable development (WOUGNET, 2023)

Through their mission to promote and support the use of ICTs by women and women organisations in Uganda, they want all women to take advantage of the opportunities presented by ICTs in order to effectively address national and local problems of sustainable development. The new ICTs, in particular, email and the Internet, facilitate communication with each other and the international community. Indeed, access to information about best practices, appropriate technologies, ideas and problems of other groups working on similar concerns have been identified as critical information and communication needs of women organisations in Africa (Women in The World Foundation, 2023)

Although WOUGNET's emphasis is mainly in Internet technologies, they also carry out research in how these technologies can be integrated with more common means of information exchange and dissemination including radio, video, television and print media. As stated before, their vision is inclusivity of women and girls within the context of ICT. Through increasing their capacities and opportunities for exchange, collaboration and information sharing, they aim to improve women's conditions of life.

3. Case study data

3.1 Data collection

I collected three different types of data for the case study namely documents, most notably the book published by the organisation titled Combattre le cybersexisme (Pardo et al., 2021) and social media posts created by StopFisha as well as an interview provided by one employee of WOUGNET. In Table 5, I collated the sources of my data, showing how and when I collected them, their importance and verifiability.

Table 5. Source of data

Method of collection | Time of collection | Importance | Verifiable | |

Documentation (Book) | Online | Dec 2021 | High | High |

Social media posts | Computer assisted | May 2022 | High | Medium |

Interviews | Virtual | May 2023 | High | High |

Source: Author.

The aim was to have multiple sources of evidence used in order to strengthen the reliability of the case study. (Yin, 2018 cited COSMOS Corporation, 1983; Yin et al., 1985) states that one analysis of case study methods found that those case studies using multiple sources of evidence were rated more highly, in terms of their overall quality, than those that relied on only single sources of information. In addition, (Yin, 2018) adds that the need for multiple sources of evidence is greater for case studies than other research methods such as experiments, surveys or histories.

The documents I used (especially the book) allowed a specific, unobtrusive and stable way for me to have direct quotes attributed to the organisation without the interview process (Yin, 2018). Because it is a published piece of evidence, any quotes from it are easily verifiable and it remains accessible both electronically and physically from multiple sources like FNAC and Librarie Decitre. It served as the main source of the organisation's views for all the research questions and thus made a good source for the case study. Although the organisation also had pamphlets, their availability was limited because the access occurred only on occasions I interacted with the organisation in person. Thus they were not included in the data collected.

The social media posts were collected subject to a priori exclusion criteria with specific targets for what they should entail which was expounded upon in the setting and sample section of the methodology.

The biggest difficulty I encountered was with a section of my original plan (to carry out interviews with the Stop Fisha members). As time went on, the possibility for direct interviews was diminished because of the case study deadline. They would have served to make the case study findings in relation to Stop Fisha and conclusions more convincing through what (Yin, 2018 cited Patton, 2015) was known as data triangulation. Although numerous attempts were made to arrange for this source of evidence, unfortunately the organisation was not able to provide time for this.

(Yin, 2018) stated interviews had the potential to yield interesting insights for the case study research due to the difference in opinion between individuals, and in this case the difference between organisations across countries. Luckily enough with WOUGNET, I was able to interview one employee who worked within the organisation.

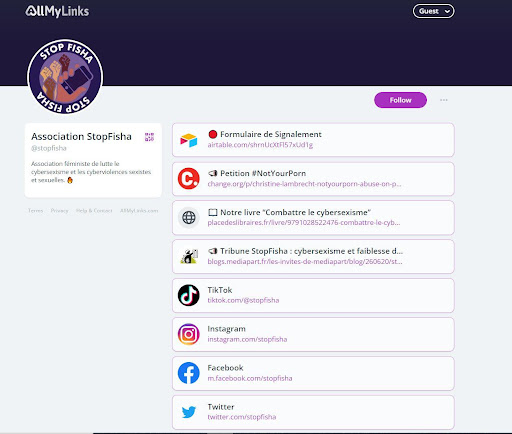

3.2 Setting and sample

Images from the organisation Stop Fisha's accounts on three social media sites were sampled—Meta, Instagram and Twitter—because two of them are part of the most popular social media sites (Statista, 2022). In addition, the organisation utilises them as part of their social media presence as shown in Image 1 below.

Image 1. Association Stop Fisha's social media presence

Source: AllMyLinks.

(Mumby et al., 2017) stated that the methods chosen for the data analysis has a bearing on how the connections between the different resistance practices and intents (particularly infrapolitics and insubordination) may translate into collective forms of insurrection. Every decision made about the data collection process will thus be justified accordingly.

It is important to first consider that qualitative research tends to use smaller samples than quantitative research, and as such there are no rules for sample size in qualitative inquiry' (Patton, 2002 as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2013). The sample sizes could range from a single participant or text being analysed in depth (e.g. see Crossley, 2007, 2009 as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2013) to a size of 15 to 30 individual interviews to identify patterns across data (e.g. Gough & Conner, 2006; Terry & Braun, 2011a as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2013). For interviews, more than 50 interviews would constitute a large sample in qualitative participant- based research (Sandelowski, 1995 as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2013).

Despite the existing evaluation of the sampling options for periodical media content, the traditional sampling technique is applicable to social media data is largely under-explored (Kim et al., 2018). For this study, purposive sampling was used. This involved selecting data cases (participants, texts, images) on the basis that they would be able to provide ‘information rich' analysis for the study (Patton, 2002 as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2013). This, criteria for the data collection was decided as shown below and the images were downloaded on one day in 2022 for two reasons; to prevent overwhelm because there was only one researcher and because the organisation's data was limited in quantity given the a priori exclusion criteria stipulated for the case study. A priori exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Posts that were reposts/retweets of another organisation's content, because the aim was to understand Association Stop Fisha's data as distinctly separate from other organisations as possible.

- Posts from the year 2021 because the book provided a detailed enough source of data from that time period.

- Posts from individual members of Association Stop Fisha that were featured on any of the pages because the study was investigating the organisation as a whole.

When considering the inclusion criteria, particularly the time period for which to consider for the collection of social media data, the study relied on (Kellogg, 2009 as cited in Mumby et al., 2017)'s assertion that longitudinal and ethnographic methods (Courpasson, 2017a as cited in Mumby et al., 2017) enabled a more thorough understanding of how resistance unfolds over time and space. It was posited that this can provide insights into how micro-political forms of daily oppositional practices might be “scaled up” (Hardy, 2004 as cited in Mumby et al., 2017) to collective forms of struggle (Kelly, 1998 as cited in Mumby et al., 2017) as well as how the thousands of petty acts (Scott, 1990 as cited in (Mumby et al., 2017)) might in themselves result in major change.

The inclusion criteria for social media posts used in the study were as follows:

- Posts on the organisation's social media accounts, not the personal accounts of any of the members of the collective.

- Content shared repeatedly across more than one of aforementioned social media platforms was only counted as once.

- The period of consideration was January 2022 to May 2022.

Thus after consideration of the different factors and criteria considered, a sample of 50 images was collected. As it was not the only source of data for information from the organisation, the sample size was deemed sufficient.

While gathering the images it was important to distinguish between the various months in which they were posted by Association Stop Fisha organisation. Different folders were set up with each month titled accordingly [Month 2022] and the posts from each month collectively downloaded into the respective folders.

When deciding on the data from the book, I again opted for purposive sampling, the a priori exclusion criteria was as follows:

- The consequences of gender and sexual cyber violence as this was not the target of the case study.

- Sections detailing the legal aspects of cyber violence such as ‘The actors of cyberspace regulation' and ‘What the law says' under the different categories of cyber violence because the case study is not an analysis of the law.

- The sections talking about advice for the victims and relatives because it was not the target of the case study.

- Sections from the introduction giving general information on the context and setting.

The sections of the book sampled for the case study were as follows:

- For the sections ‘Introduction', ‘Cyberspace' and ‘Cyber sexism', the purple boxes which contained notes and observations from the organisation.

- Within the section on ‘Gender based and sexual cyber violence', the definitions of the various categories of cyber violence (usually the first two or three pages).

For the organisation WOUGNET, I interviewed one employee virtually in May 2023 as the study is an introductory inquiry into what gender and sexual cyber violence looks like cross culturally.

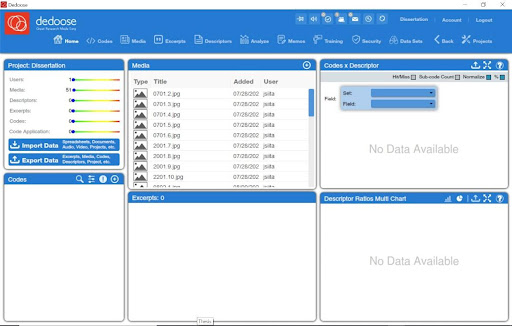

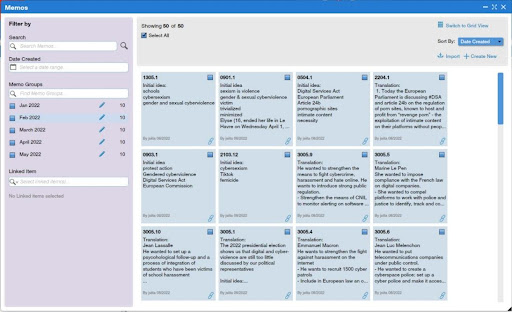

4. Data analysis

Because the images I gathered and the book needed to be analysed simultaneously, I decided to utilise Computer Assisted Qualitative Analysis Software (CAQDAS) for the coding. There are numerous choices on the market with many covering both text and video-based data (Yin, 2018) such as Atlas.ti, Nvivo, Delve and HyperRESEARCH. For this analysis, the aim was a high level of analysis with ease of use, reasonably priced and a short learning curve. I used Dedoose (as shown in Image 2) to analyse both the images and textual data because it fulfilled those requirements.

Image 2. Dedoose Software Interface

Source: Dedoose Software 9.0.54.

Despite the ease and quickness of these tools, they are still just tools meant to reliably assist in creating outputs such as the occurrence of words or codes (Yin, 2018) and conduct searches for multiple combinations of codes in the data. Armed with the knowledge that the outputs were not the final step of my analysis (Yin, 2018), my direction for data analysis took one direction; thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organizes and describes the data set in (rich) detail. However, frequently it goes further than this, and interprets various aspects of the research topic (Boyatzis, 1998 as cited in Braun and Clarke, 2006).

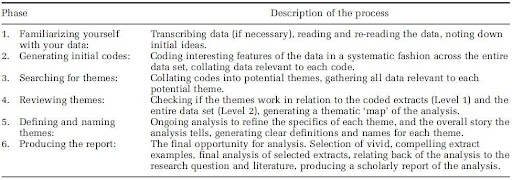

After collecting the images from social media and reading the book, I used the research questions as the jumping point for decisions on data analysis. Data analysis followed the phases as depicted in Table 6(Braun and Clarke, 2006)(Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Table 6. Phases of thematic analysis

Source:(Braun and Clarke, 2006), p. 87

For the first phase, as a way to get started with familiarizing myself with the data, I took copious notes both by hand and within the data set itself. Using memos (as pictured in Image 3),

Image 3. Memos taken while familiarising myself with the data

Source: Author using Dedoose Software 9.0.54.

This was the beginning of my analysis building as I wanted to remember what initial ideas I had when I started generating my initial codes for the second phase. These memos also served as hints, clues and suggestions for ways to interpret the data and connect the ideas I would end up having later on (Yin, 2018). While continuously reviewing the data from the social media and book, I occasionally noted descriptions however I did not do this strictly throughout the entire process as I knew I would consolidate the codes into themes during phase 4.

Reaching the second phase, my coding strategy was to start with the images then move onto the book and code the samples specified in 3.2. This process yielded a total of 72 codes (11 parent codes and 61 sub codes) which I proceeded to check recode for phase 4.

Phase 5 involved exporting the codes into a word document to compare the golden threads running through the various codes. I consolidated the most similar sub codes and continued to refine my themes to end up with 3 big themes with 12 sub codes. From this I was able to reduce the themes down to one theme.

For the interview data, I also used the process of thematic analysis as it as the most straightforward and time conscious method for the case study.

4.1 Ethical considerations

I had planned to interview members of the organisation after informally meeting a selection of them at 24H contre les violences sexists et sexuelles, a 2 day conference held by Theatre Des Célestins in Lyon in November 2021. Though I reached out in February and again in April to schedule the interviews, I was unsuccessful so I worked with only data collected for the case study instead i.e. images from social media and the book written by the organisation.

Meta and Instagram's copyright policies only allow the ability to post content as long as it does not violate someone else's intellectual property rights (Instagram Help Center, no date). Therefore, as I only needed the images for my own private use in education I did not need to repost or re share them on any social media.

(The European Union Intellectual Property Observatory, 2022) notes that it is possible to download a copy of a work from the internet, in accordance with the private copying exception, such as private use if the source of the copy is lawful. In addition, the downloaded copy must not be shared afterwards. In keeping with the appropriate copyright restrictions, I will not reproduce the images used in the analyses presented here. The images can be found on the organization's social media platforms with Meta, Instagram and Twitter under the user name @StopFisha as seen in Image 1.

The book (Pardo et al., 2021) titled Combattre le cybersexisme, was purchased with my own means, and again in accordance with the (The European Union Intellectual Property Observatory, 2022) I limited my analysis as described in Part 3.2 and quotations of the book for only specific purposes i.e. educational with the source of work and author names always mentioned.

4.2 Limitations

It was more difficult to find data meeting the a priori exclusion criteria on Twitter, than on the other two social media sites Meta and Instagram. This could be because of Twitter's interaction model being more conversational i.e. responding to other tweets and retweeting can make up the bulk of an account's interactions. As such, majority of the organization's data from Twitter was excluded because it was mainly interactions amplifying or commenting on other organisations' content not original tweets fulfilling the criteria.

The CAQDAS software used (Dedoose) while easy to intuit and begin using was not useable while offline. Because the data was inaccessible without the internet, it is not recommended to researchers with irregular internet access.

5. Presentation of results (Stop Fisha)

From my analysis of the data from Stop Fisha I made a number of observations. The first was that while the case study aimed to treat the book and social media data as one data set, there was a difference in the portrayal of cyber violence depending on the data source. In the book, there was an increase in detail of description of the various cyber violence. This was expected because the use of social media limits verbosity i.e. limits in Twitter characters to 280, max 10 Instagram images for a post.

The overlap of cyber violence was incredibly prevalent i.e. some types of cyber violence involved the other for example; pedocrime usually begins with grooming, sextortion can result from the doxing and dissemination of intimate content and hacking can lead to identity theft and catfishing.

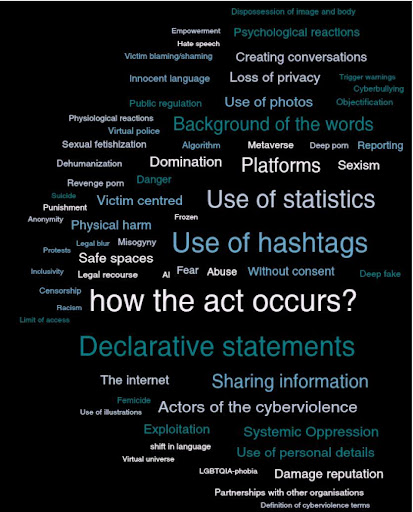

During the data analysis, I used Dedoose to generate a word cloud that is pictured below. It is useful to understand the how the different codes and sub codes were eventually refined into two themes by providing the big picture of those codes.

Image 4. Word cloud generated during the analysis

Source: Author using Dedoose Software 9.0.54.

The theme I was able to deduce from the book and social media data was a victim focused approach interspersed throughout the Association Stop Fisha's communications (social media and book).

In their data, Association Stop Fisha sometimes reflects in a positive light by showing a desire through empowerment and inclusivity to the victims but also by trying to shed a truthful light on not only their victims but those around them that are affected by the gender and cyber violence experienced. While breaking down the definitions of the different types of cyberviolence, Association Stop Fisha used a mixture of elements including the background of the cyberviolence which could be related to its meaning or origin, the actor of the cyberviolence and details of how the act takes place/ is enacted.

Furthermore, their data showed that there is a now an equalization between real life and cyber space in terms of the effects of the actions on cyberspace and the severity of the activities that happen. Some of the effects experienced by women included but we not limited to, damaged reputation, dispossession of image and body, limited access, loss of means, loss of privacy, physical harm, psychological side effects and death.

We also see that in understanding these effects there comes to be an equalization between real life and cyber space in terms of the effects of the actions on cyberspace and the severity of the activities that happen.

6. Presentation of results (WOUGNET)

WOUGNET's data was provided from an interview conducted with an Assistant Technical Support Officer. She works as a digital literacy and security trainer for the organisation and has also led various projects for the organisation to end online harassment among women journalists.

According to her, the most common types of online gender based violence they encounter among women in Uganda are online stalking, non-consensual distribution of intimate images, online grooming, doxing and trolling. She also mentioned a prevalence in these kinds of attacks being more frequent among women in the urban areas as opposed to rural areas. She added that it was due to those in urban areas having easier access to technology and mobile phones. For the purposes of this study, urban areas are considered the major cities all over Uganda such as Kampala, Jinja, Mbarara, Kabale, Fort Portal, Mbale.

In terms of activities carried out by WOUGNET against gender and sexual cyberviolence, there were two main activities namely research, advocacy and awareness raising, capacity building and policy engagement. She mentioned their online and in person campaigns that they carried out to share information about online gender based violence where the aim was educate the community on the different types of online gender based violence and their impacts to the people who experienced them. Some of these online campaigns took place over social media and others were in person through engagements across schools. Through the use of art, tech pop ups, the organisation continues to spread knowledge on online gender based violence to girls and young women. Their advocacy included creating a toll free line for the victims to call and report their experiences, ask questions and be connected to the necessary authorities when necessary.

The capacity building was a two pronged approach; first teaching women to use the digital technology and then later on teaching them how to be safe online especially in areas where the knowledge of digital technologies is not as prevalent. For policy engagement, this involved meeting with different stakeholders such as law enforcement and law makers to bring about high level discussions on online gender based violence.

Part 3: Discussion

Introduction

The case study's objective was to understand how gender and sexual cyber violence are portrayed, and the activities the organisations use to tackle cyberviolence within the context of resistance. The discussion will explore the answers to these questions from the point of view of each organisation through the themes generated from the findings respectively, then a discussion of the resistance context of each along with recommendations for the problem along with the conclusion.

1. Association Stop Fisha

1.1 How is Association Stop Fisha portraying cyberviolence?

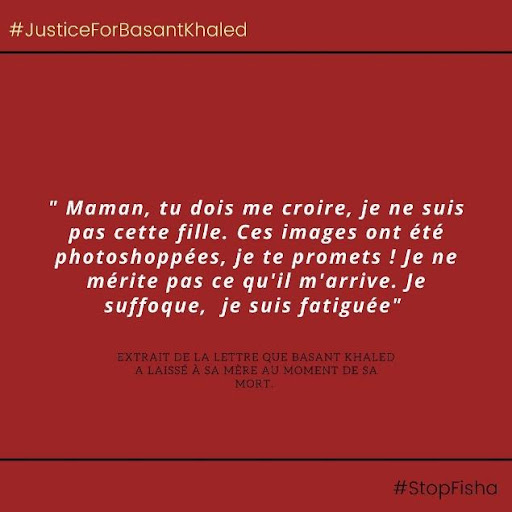

From a thematic analysis of Association Stop Fisha's social media and book data, we start to understand the picture that this organisation paints in relation to cyber violence. Overall, their communications harbour a focus on the victims of cyberviolence whether by highlighting positively through empowering them and being inclusive or employing fact based personalization. Throughout both of these ways, we can see the equalization of cyberspace and real life because the effects of these violence within the cyberspace spill over to affect women's lives offline.

An example is the quote below which although does not use the word victim, it brings to the forefront of mind what kind of effects the cyberviolence at hand has on the person experiencing it.

“The person whose identity has been usurped: the perpetrator of the offense can harm their image, their tranquillity and their well-being, this is particularly the case when the usurper creates an account in the name of the victim on a porn website. » (Pardo et al., 2022, p. 156).

This excerpt is in relation to the act of identity theft. It goes even further by saying:

“The person who is deceived by the use of the false identity: by pretending to be another person, the usurper will often scam a third person, by extracting information or money from them. This technique is used in particular by child criminals to approach their victims. » (Pardo et al., 2022, p. 156).

These excerpts in relation to identity theft make it clear that the victims who experience this kind of cyberviolence can fall into different categories, either having their identity stolen or by being deceived by a perpetrator and in either situation, it is made clear that the occurrences are not the fault of the victims. This kind of language is helpful in shifting victims' perception of themselves after experiencing the kinds of variations that can occur in a situation as common as identity theft. In this way, we see that the book Combattre le cybersexisme is not only an information guide but another way that Association Stop Fisha works to offset the effects of gender and sexual cyberviolence and the victim blaming that usually arises from violence in general.

With the definitions of the different gender and sexual cyberviolence terms, the book breaks these down into three parts namely the background of the term where applicable, the actors who perpetrate the cyberviolence and how it occurs. This kind of breakdown is shown in the table;

Table 7. A breakdown of acts of cyberviolence in Stop Fisha's Combattre le cybersexisme

Term | Background of the words | Actors of the violence | How the act occurs? |

Blackmail on cam | Blackmail that occurs on camera/ through the use of technological devices | A man pretends to be a woman in order to trick another man and steal sexual content from him and then blackmail him. People who use this technique are called grazers. | Another cam blackmail technique is to create a fake virtual profile2 and get in touch with anyone on the internet, often through a dating website. As the exchanges escalate, the aggressor invites the victim to continue with a more intimate video conversation and will record their textual and visual exchanges without the consent of the person concerned. |

Catfishing | n/a | Someone hides their identity by pretending to be a friend, a classmate, a possible lover or even a fictitious character | Done in order to facilitate a relationship. It usually happens a lot with grooming. |

Cum tribute | An English word that translates to “sperm” and the term tribute means “homage”. | The person takes pleasure in photographing the result: the photo of the person covered in sperm. | The act of masturbating and ejaculating in someone's photo. |

Cock tribute | Cock is an English word that means “penis”. | The perpetrator takes a photo of his penis – often erect – next to someone's photo. | This photo will then be disseminated and sometimes sent to the person who appears in it. |

Creepshot | In English, shot means “cliché” or “photo” and the derogatory word creep means “dirty guy” or “weird guy”. | Someone takes the photo without consent. | This photo could be taken while they are walking down the street or lying on a beach, for example. |

Cyberbullying | A form of harassment carried out electronically including by telephone, email and social networks | An individual or group of individuals | Cyberbullying can take several forms: the multiplication of phone calls or written messages or even flaming |

Cyber outing | Forced outing or coming out is the act of revealing the sexual orientation (lesbianism, homosexuality, bisexuality, asexuality, etc) and/or gender identity (non-binary, trans identity, intersex, etc.) of a person without their consent | outing by a person from the LGBTQIA+8 community; and outing by someone who is not one of them and who is, in most cases, LGBTQIA+-phobia. | Such information can thus be communicated to their relatives, to their employer, in the newspapers, and/or on cyberspace. |

Deep fake | The result of the contraction of the words deep learning and fake. | A successful montage is claimed as a “masterpiece” by its creator, but for the victim, it is a nightmare | A montage made from a photo, video or recording, which has the particularity of being so successful that you do not realize that the image is faked. |

Deep porn | A form of sexual deep fake | An anonymous creator/group | Taking a person's face and replacing their body with that of a naked body that is not their own. The montage is then massively disseminated on the Internet. |

Dick pics | An English expression that literally means “penis photo”. | Can be anonymous or known to the victim | Sending a photo of a penis to a person without their consent therefore imposing the image on the sight of the recipient without giving them the choice to see it or not. |

Doxxing | an English term designating the disclosure of personal data on the Internet relating to the private life of a person with the aim of harming them | individual | This may include revealing where they live, work or study, and may go as far as leaking their banking information, for example. |

Flaming | n/a | In the vast majority of cases a “proximity violence”. Thus, the victim often knows their perpetrator, the latter may be a classmate or a student from the same school. | Refer to trolling and cyber bullying |

Fisha account | An account called “fisha”, verlan of the term “poster”, is an account or a group created on a social network, a platform or a messaging system. Fisha accounts often bear the name of cities, departments or neighbourhoods in order to list and centralize the victims and to be able to identify them more easily. They are called: “fisha78”, “affichepute_rouen”, “salopedu95”, etc. | By calling themselves “judges”, the “fishers” (those who manage the fisha accounts) and viewers sanction the victims by taking them to court in the public cyberplace. | The content published without the victim's consent is often accompanied by their personal information such as their name, their first name, their identifiers on social networks, their telephone number, their school's name or their address. Concretely, the victims' content is shared and re-shared. |

Grooming | n/a | By discussing with the victim, the pedophile can choose to assume his identity with her. He can also hide his identity by pretending to be a friend, a classmate, a possible lover or even a fictitious character in order to facilitate grooming: this is what is called catfishing. | We speak of grooming when a pedophile targets his victim and discusses with her in order to build a friendly and/or romantic relationship and thus, to create an emotional connection with the aim of coaxing them and persuading them to have physical or virtual sexual relations with him (examples: sexting, sending intimate images or videos, sexual blackmail and/or threats). |

Hacking | n/a | The actor does so in order to take control of it or to access a person's personal information and data and then to exploit it. | A set of computer manipulations make it possible to enter a computer system (telephones, computers, etc.) |

Happy slapping/ video lynching/ video aggression | In English, this expression literally means “to slap happily” and it is a pun on the expression “slap happy” which refers to a cheerful and good-natured attitude. | The person does so with the aim of inflicting even more humiliation on the victim. | A practice that consists of filming a physical or sexual assault and disseminating the images |

Identity theft impersonation | The use of another person's identity without their knowledge | Without the consent of the victim, the actor will use personal information that allows them to be identified e.g.name, telephone number, date of birth, address, photographs, etc. | Identity theft usually begins with the collection of personal information about the victim. It happens that acts of identity theft follow acts of piracy or hacking. However, identity theft can also occur as a result of forgetting to log out or sharing a password with a friend or boyfriend. |