History of labor trafficking

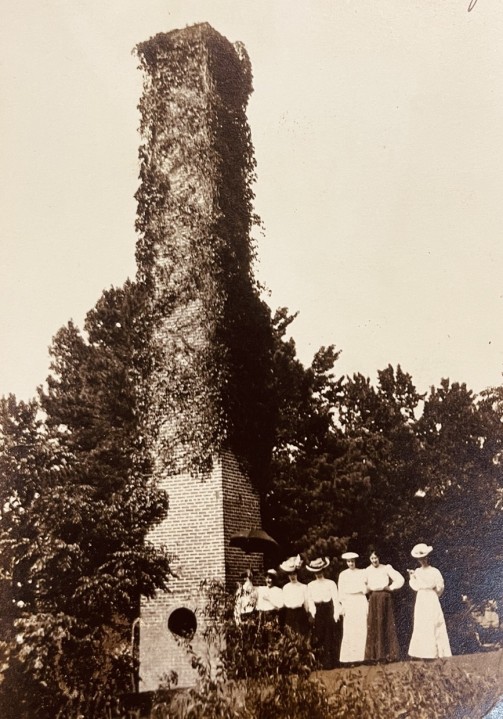

ARIZONA, La. (KTAL/KMSS) – The kids ran circles around the old brick chimney, yelling “You're it,” at one another until they tired and headed back to the front porch of the crumbling mansion—but if the children had known the truth about the chimney in the middle of that Claiborne Parish field, would they have used it as the base in their game of tag?

And if you learn the truth about that old chimney, will it change the way you feel about a major source of human trafficking?

The truth about the chimney

The truth is that child labor existed in northwest Louisiana long before Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, arriving in the region well before the late 1800s when the first known factory in north Louisiana was built in Arizona.

That's Arizona, Louisiana, for those who aren't familiar with Claiborne Parish history.

But the history of rural Claiborne Parish is further proof that human trafficking is nothing new to any region of Louisiana.

“In 1900, 25,000 of the nearly 100,000 textile workers in the South were children under 16. By 1904, overall employment of children had increased to 50,000, with 20,000 children under 12 employed,” according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (USBLS). “As one mill owner remarked, working 12-hour days, 6 days a week left children ‘no time to spend in idleness or various amusements.'”

Child labor had already been woven into the fabric of American clothing, sheets, curtains, shoes, and furniture cushions since before the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, and continued as a result of the European invention of the textile mill in the 1700s. The first factory in America, a textile mill, was located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and opened in 1790. This sped up the world's hunger for cheap textiles.

Human trafficking existed on such a large scale after the invention of the textile mill because society became insistent on low prices for textiles. The hungry mills gobbled up cotton faster than it was being grown at first, and enslavement was thought of as the solution to the need for cheap labor in American cotton fields. There is a reason textile mills have been called “a Herod among industries.”

In fact, in 1842 a law was passed out of necessity in Massachusetts that prohibited children below the age of 12 from working more than 10 hours a day. Everett Lord wrote in 1908 that probably in every factory town at least seventy-five percent of the employees are children. All the cotton from the South had to go somewhere, and it was going to those who wanted unrefined materials for their textile mills.

The majority of the textiles in this nation pre-war were centered in New England, and those textile mills were buying cotton that was produced by trafficked people. It took a lot of children to work the cotton into thread and cloth in New England. The fieldwork was hazardous, and the factory work was dangerous, too. Kids often died young because of the lung damage they received by breathing in the cotton dust that hovered in the air because of the spinning process.

By the beginning of the Great Depression textile mills were spreading across the south, and almost half of American teens ages 14 to 17 dropped out of school and went to work. Child labor was considered normal, and few Americans spoke out against it.

The textile mill in Arizona, Louisiana is interesting to historians because it was rejected by locals. Questions still remain about whether its failure was caused by location, culture, a combination of both, or other factors. But what does matter is that the first-known attempt at child labor in a textile mill failed in northern Louisiana, specifically in Claiborne Parish.

Dr. William Barclay, a prominent Scottish author, and minister born in 1907, wrote of child labor in Scottish textile mills.

“…deep in the unconscious memory of people the impression of these bad days is indelibly impressed. Whenever people are treated as things, as machines, as instruments for producing so much labour and for enriching those who employ them, then as certainly as the night follows the day disaster follows. A nation forgets at its peril the principal that people are always more important than things.”

In Arizona, Louisiana, some viewed factory work as unethical when the textile mill was built in the late 1800s, because homesteading was the most common way of life at the time.

T. H. Harris is the former Superintendent of Public Education for the State of Louisiana. His memoirs detail his childhood in Arizona, Louisiana, and his time working as a child laborer at the textile mill.

“The workers in the old cotton factory were, in the main, young girls and a few young boys. I think they were all white and from tenant families in the main, or imported,” he wrote.

Harris also detailed that his mother was advised to let his family starve, if necessary, but not permit their good name to be besmirched by making factory workers out of Aussie and himself.

“That attitude may have had something to do with the failure of the factory,” he wrote.

Later, the lack of jobs for adults during the Great Depression exposed the harm child labor was causing to the United States economically. Adults needed jobs they could not get because children could do them for less money. Before the Great Depression ended, legislation was enacted against child labor. Slowly, adults began to find work again. And just as slowly, Americans forgot that children once worked full-time.

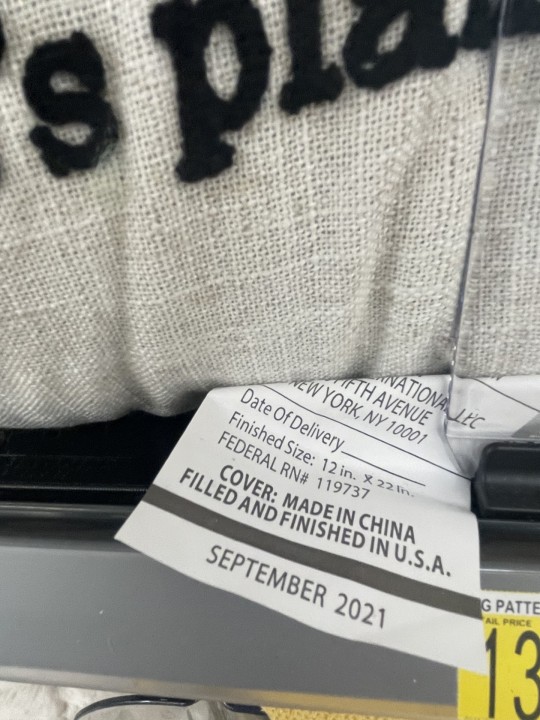

Grandma's problem is now yours

Because our children are not laboring in textile mills today, many Americans do not understand that the massive problem of child labor once existed in this nation, and that is not to say that we do not still have a smaller issue with child labor today. But the clues of a worldwide problem concerning child labor are hidden in plain sight all around us today: $9 dresses, $4 t-shirts, $12 shoes. Even some of our high-end brands on American store shelves purchase textiles produced at overseas factories that employ children or force people to work.

Research the tags in your closet and you will likely find that you wear clothing that comes from countries where child labor or forced labor is legal.

But Americans have not consciously decided to perpetuate the old system of human trafficking. We were born into this system. And we are blessed to be a part of the generations with the capacity to end it.

Hurt people hurt people, even if by accident

Our ability to feel empathy for others is one of our greatest societal strengths.

What if we contemplate the possibility that our own poverty impoverishes others half a world away? We can do for them as we would want others to do for us because we are already wearing the shoes they made for us. Our connection is real.

Much must be done to correct the systems that support child and forced labor. But we are humans, and our minds, hands, and hearts are fully capable of understanding why Americans currently need cheap textiles.

So how do we begin? Step one of the scientific method has always been to identify the problem. We need to examine the reason why Americans need to buy cheap textiles.

The internal conflict

Child poverty rates are highest in American states that haven't raised the minimum wage, but an analysis by the Congressional Budget Office in 2019 showed that increasing the federal minimum wage (currently $7.25 an hour) will bring more than 500,000 children out of poverty.

There is a difference between state and federal minimum wages. Federal standards must be met by all states. But individual states can, at any time, raise the minimum wage for their people.

The minimum wage in the United States was made effective by the signature of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, during the Great Depression, but it was deemed unconstitutional, and a working minimum wage didn't go into effect until 25 cents an hour became the standard in 1938.

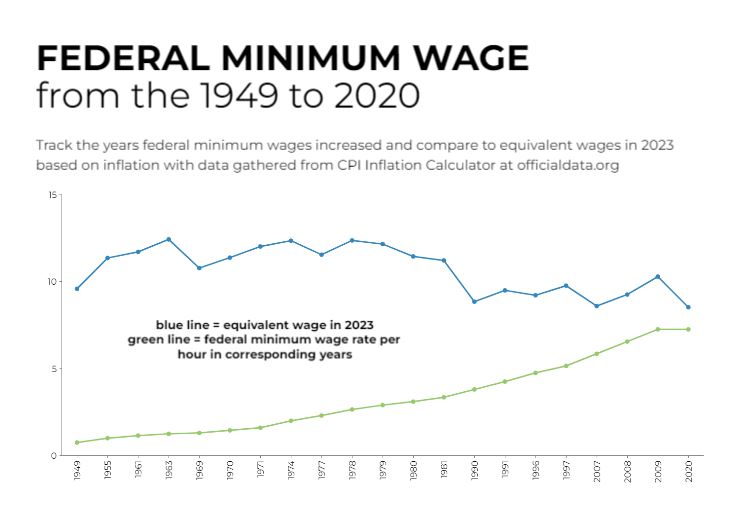

The following chart will allow you to see not only how the Federal minimum wage has increased through the years, but also how the inflation rate can be applied to outdated minimum wage rates and show us how much past wages would be worth in 2023 dollars.

You may have noticed while viewing the chart, that the minimum wage has not been raised since July of 2009. When the minimum wage is not raised in societies where some demographics (women, for instance) are prone to receiving lower wages than those of other demographics, the minimum wage can help by setting the standard for how much pay is too little.

Income inequality in America between the upper class, and the middle and lower classes, is growing significantly larger in the United States. Income inequality between men and women in Louisiana shows one of the highest disparity levels in the country.

Upper-income families have been able to build their wealth from 2001 until the present day, but lower and middle-income families have been experiencing net worths that are consistently shrinking. And with more and more single-parent homes, income inequality becomes even more of an issue.

This puts us in a situation where we need to buy cheaper goods. And when we aren't aware these goods are produced by child- and forced labor in foreign countries, the decision to buy the cheaper goods is easy. But when we do know the reason for the cheaper prices, what then?

Buying power

The buying power for past generations was significantly more than the buying power in 2023.

What this means is that past generations could buy more food, more expensive clothing, more easily afford fuel to heat their homes, afford nicer furniture, etc…, than the present generation of Americans.

But in reality, when those in poverty must resort to purchasing goods made by child labor and forced labor because it is the only way they can survive on their limited budgets, there just may be a problem.

Houston, we have a problem.

And the only way out of this problem is for people who truly care to come up with adequate solutions to the complex economic structures that have absorbed the lower and middle classes.

Here is a closer look at the situation.

Fast fashion

Fast fashion happens because fashion trends change quickly and clothes are produced just as quickly to keep up with the demand. Consumers buy fast fashion and wear the garments quickly, often only a few times before the clothing is discarded because fashion trends are ever-changing.

Fast fashion is a source of ecological damage and a large percentage of the world's forced and child labor. Many workers must work six to seven days a week, 12 hours a day, just to make enough to provide the basics for their families. And many of those workers are children.

Though child labor was made illegal in the United States via the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, textiles produced by children in countries where child labor has not been abolished flow into this nation constantly and are sold without labels that identify child labor in the production processes. And it will take all of us, says U.S. Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh, including governments, businesses, unions, workers, and civil society, to eliminate egregious labor abuse.

At the moment, the economy has control of the middle and lower classes. We all know this was not the American Dream of our forefathers.

But there are ways to create change, and one of those ways is the concepts found in the Clean Clothes Campaign.

The Clean Clothes Campaign

The Clean Clothes Campaign believes the “public has a right to know where and how their garments and sports shoes are produced.” They call for action to see that workers' rights are respected, but do not “generally endorse or promote boycotts as a tool for action.” They believe Governments have a duty to protect workers' rights, to hold companies accountable for their business practices worldwide through legal and regulatory instruments and policies to ensure workers' rights are respected, and to provide access to remedy and redress to workers in cases of violations of their rights.

Sweatshops that employed women and children in the late 1800s and early 1900s in America were paying workers nonliving wages—wages that did not give workers the ability to pay for the necessities they needed to simply live, even though they were working long hours. It took progressive Americans to reform and create U.S. labor, state, and local laws.

Events such as Chautauquas, which Roosevelt called “the most American thing about America” helped people across the nation connect with one another to make positive social changes.

And it will take much to create new laws that change our import policies and procedures, though it is possible. History proves it.

Transitional strategies

Knowing that one person cannot change the riptide of human trafficking that pulls beneath the surface of society is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, we can become numb to reality because human trafficking seems so big and we, as individuals, feel so very small. But we always have the ability to make choices that align our beliefs with our lifestyles.

For some, that choice may be to steer away from or out of sex trafficking. For others, buying secondhand clothes while researching and, eventually, supporting clothing and shoe companies that make ethical and sustainable business decisions may be the change they can accomplish in their lives.

Micro-investing in companies that make positive differences in the world of textile production may be the answer for some.

Others, still, may realize their dreams of being a therapist and make a more obvious difference in helping the trafficked.

We have the ability to create change, even if we are one of the kids who once unknowingly played chase around an old chimney that was part of a factory where little children once worked away their childhoods. For this nation was founded upon civil discourse as a means to freedom.

And it is still possible, in this free nation, to end–or at least drastically abbreviate–human trafficking. We can speak up and tell our elected officials these issues matter a great deal to us.

Click here to contact your U.S. Congressman, U.S. Senator, Louisiana Legislator, Texas Legislator, Oklahoma Legislator, or Arkansas Legislator.

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

Fair Use Notice: The PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault is dedicated to advancing understanding of various social justice issues, including human trafficking and related topics. Some of the material presented on this website may contain copyrighted material, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to promote education and awareness of these important issues. There is no other central database we are aware of, so we put this together for both historical and research purposes. Articles are categorized and tagged for ease of use. We believe that this constitutes a ‘fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information on fair use, please visit: “17 U.S. Code § 107 – Limitations on exclusive rights” on Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.

EYES ON TRAFFICKING

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.