John Brown’s Subterranean Pass-Way

Read FERGUS M. BORDEWICH's original post, from January 14th, 2006.

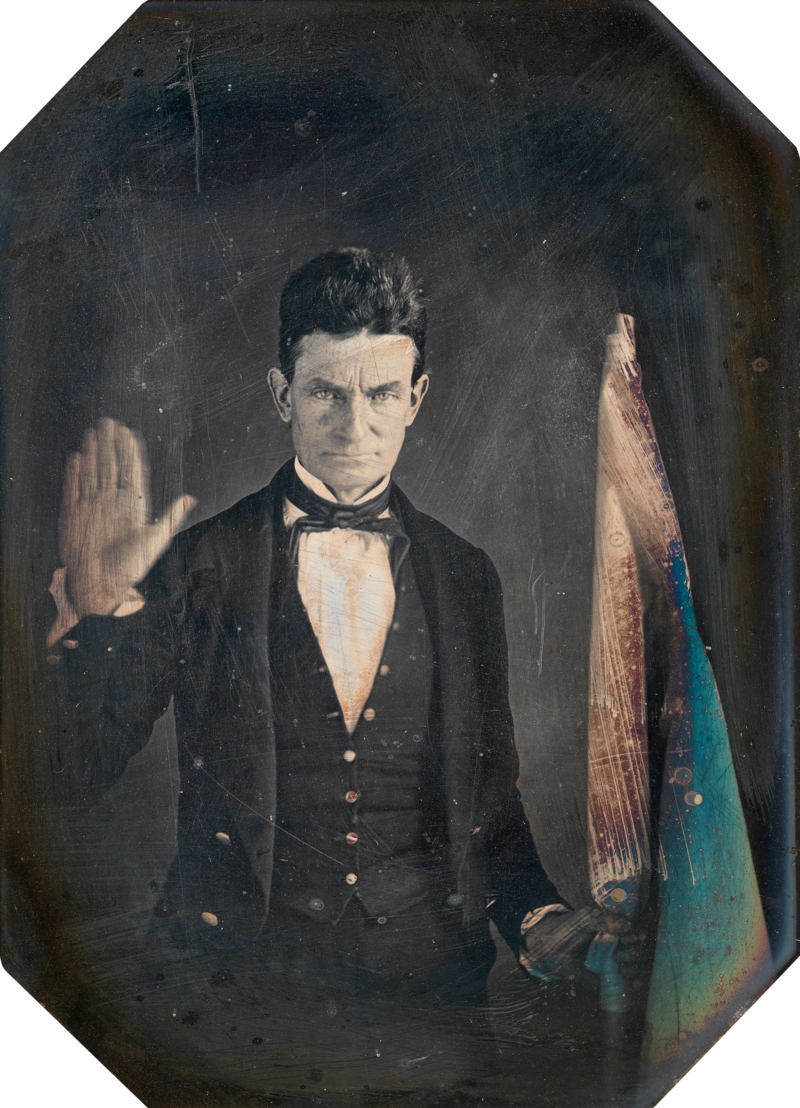

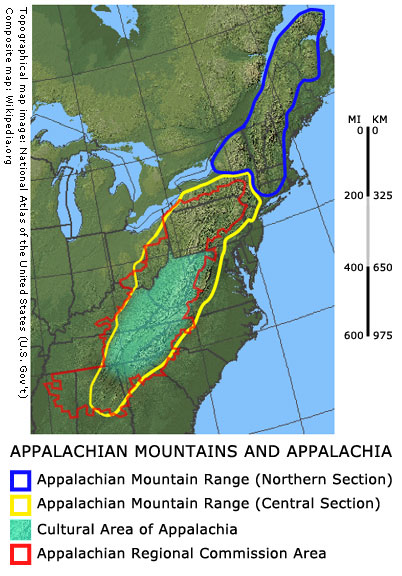

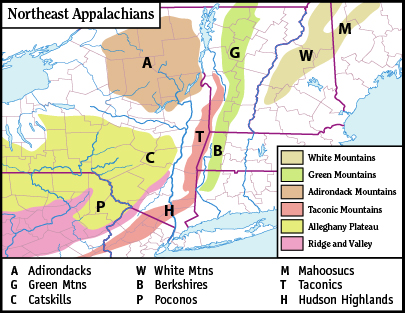

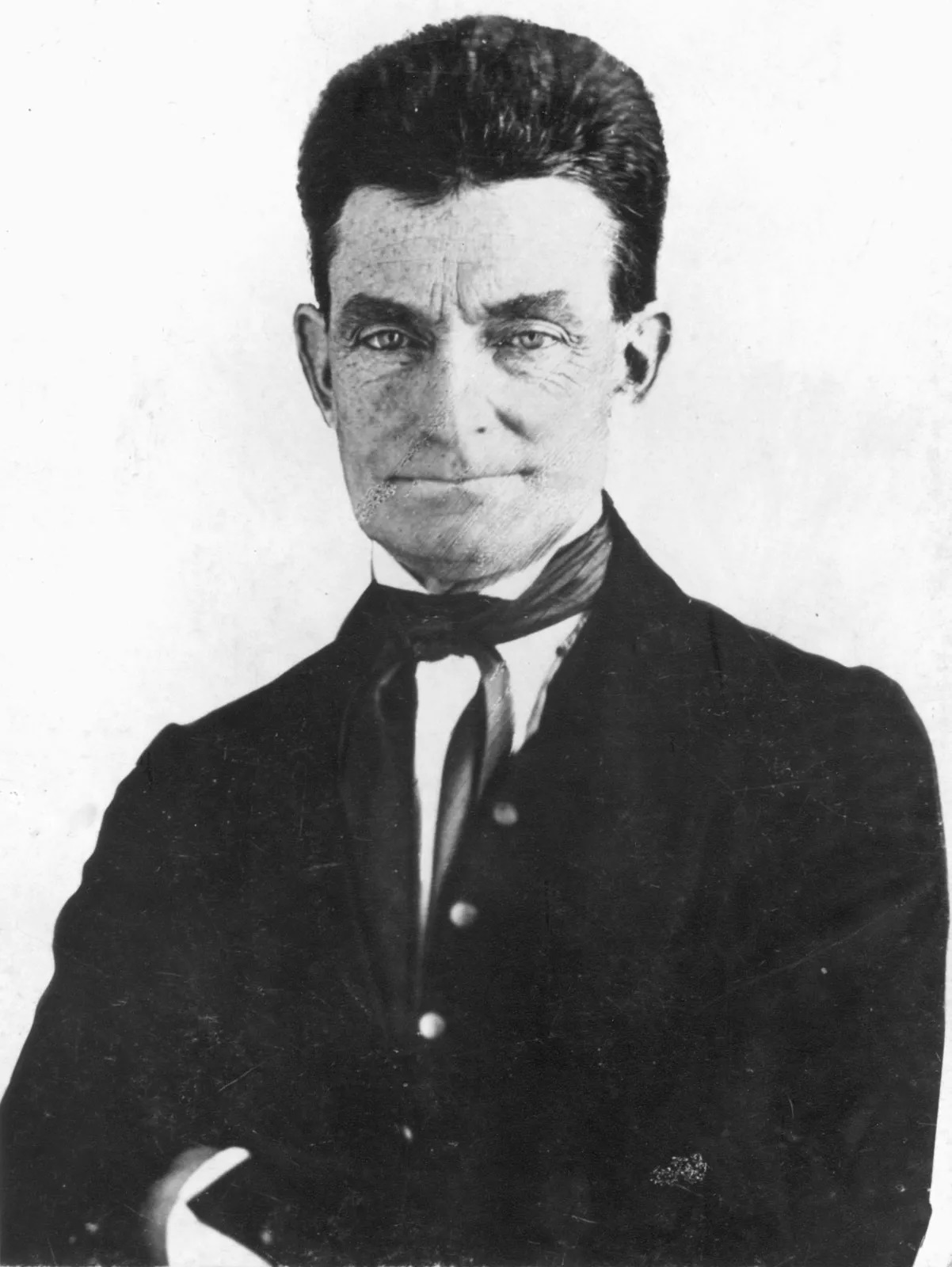

JOHN BROWN believed that God himself had ordained him to bring an end to slavery. Achieving his goal hinged on a radical and deeply secret scheme: the establishment of an “Underground Pass-Way” that would extend the Underground Railroad more than a thousand miles southward through the Appalachian Mountains into the heart of the Deep South. This highway to freedom would drain the South of slaves, Brown believed; they would travel north to the free states protected by strongholds manned by armed abolitionists and freed slaves. Few abolitionists knew what Brown really had in mind. Brown's dreams ended in the debacle at Harper's Ferry.

Subterranean Pass-Way

What was John Brown's Subterranean Pass-Way? As Brown envisioned it, it would be an underground highway that would reach 2,000 miles all the way down through the Appalachian Mountains through Virginia and Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and into the Deep South, as far as Georgia. It was the vision that Brown had in mind when he marched into Harper's Ferry in 1859 (editor's note: more on this later). This was the UGRR on an epic scale. Had [Harper's Ferry] succeeded, today we'd all be talking about how the entire underground as we know it was just the lead-up to John Brown's monumental plan.

What did Brown really have in mind? How would the Subterranean Pass-Way have worked? Was it was just a pipe dream, or something that could really have happened?

Some perspective

FIRST, LET'S PUT the Underground Railroad in perspective. Apart from sporadic slave rebellions, and individual acts of defiance, only the Underground Railroad physically resisted slavery. It was the nation's first interracial political movement. From its beginnings, it was a collaborative movement involving free blacks, anti-slavery whites, and even slaves.

It was also the nation's first great movement of mass civil disobedience since the American Revolution. It engaged thousands of citizens in the active subversion of federal law. And it was the first American mass movement that asserted the principle of personal, active responsibility for others' human rights.

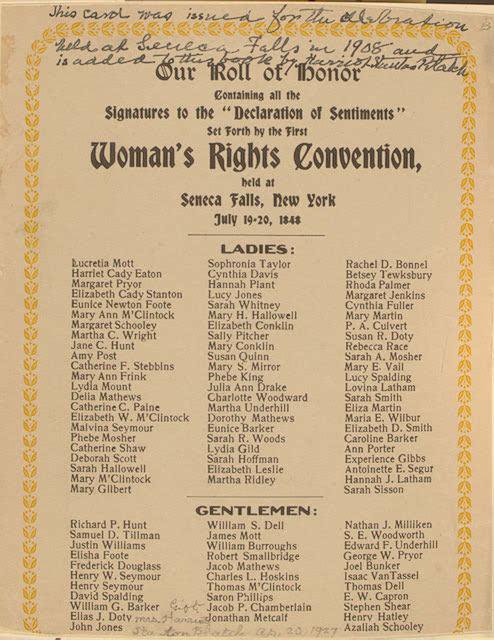

The Underground Railroad and the broader abolition movement were also the seedbed of American feminism—all the women who helped organize the first women's rights conference in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848 came out of the Underground Railroad. In the underground, women were for the first time participants in a political movement on an equal plane with men, sheltering and clothing fugitive slaves, serving as guides, risking reprisals against their families, and publicly insisting that their voices be heard.

The start of the Underground Railroad (UGRR)

The UGRR began in Philadelphia in the 1790s into a national network spanning the northern states. Why then? Why there? Philadelphia was the first place in America that offered the human synergy that made the UGRR work: large populations of emancipated blacks and anti-slavery whites (Quakers in this case). (editor's note: learn more about Quakers and abolition here.) There could be no UGRR until there were havens to which fugitives could be safely delivered. There were none until the 1790s—the region around Philadelphia was the first safe haven in the US.

THERE WAS of course never any president of the underground, no board of directors. It was a diverse, flexible, efficient system with no central control. It was a model of democracy in action, operating with the maximum of grassroots involvement. As a station master in Ohio, put it, “There was no regular organization, no constitution, no officers, no laws or agreement or rule except the ‘Golden Rule,' and every man did what seemed right in his own eyes.”

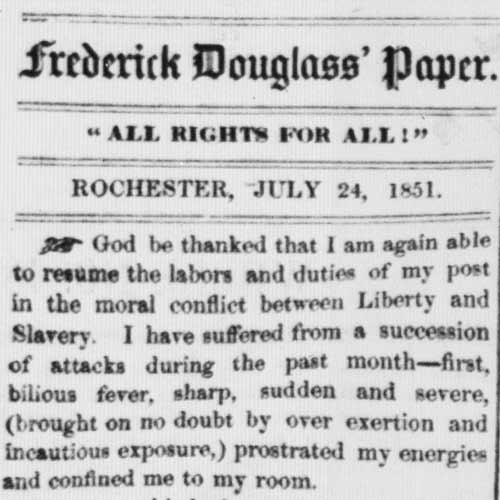

By the 1850s, in much of the North the Underground Railroad was operating with remarkable openness. Frederick Douglass' Paper, for example, regularly published detailed reports on underground activity in articles that were signed by agents themselves. In Syracuse, Jermain Loguen advertised his underground work, and his address in local papers, and identified himself on his business cards as “Underground Railroad Agent.”

To give you some context for the extent of John Brown's ambitions—he expected to free hundreds of thousands of slaves—I'll give you some figures for the kind of numbers that the UGRR actually handled at this time. Thomas Garrett, the station master at Wilmington, Delaware, one of the few to keep a tally of his passengers over a long span of time claimed to have helped a total of 2,750 over about forty years, an average of two hundred twenty-five per year. From mid-1854 to early 1855, the all-black (and predominantly female) Committee of Nine, which oversaw underground work in Cleveland, Ohio, forwarded two hundred and seventy five fugitives to Canada, an average of one per day. The Detroit Vigilance Committee, possibly the busiest in the United States, reported 1,043 fugitives crossing to Canada from May 1855 to January 1856, an average of one hundred thirty per month.

A familiar passway?

In 1858, Brown wrote to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a Boston abolitionist: “Rail Road business on a somewhat extended scale is the identical object for which I am trying to get means. I have been connected with that business as commonly conducted from my boyhood…”

“Rail Road business on a somewhat extended scale is the identical object for which I am trying to get means. I have been connected with that business as commonly conducted from my boyhood…” — John Brown

Brown's family had engaged in underground work out of their home in Hudson, Ohio—a rabid abolitionist town—since the early years of the 19th century. Fugitives were hidden in the Browns' barn. And as a young man, Brown himself traveled around northeastern Ohio guiding fugitives. At the age of thirty-seven, he had taken a personal vow before God to consecrate his life to the destruction of slavery. Not long before the Harper's Ferry raid, he told Harriet Tubman that the Day of Judgement was at hand, that it was time for “God's wrath to descend,” and that he was the divine instrument ordained to deliver it.

Brown may have begun thinking about a Subterranean Pass-Way as early as the 1840s, when he worked for a time as a surveyor in the mountains of western Virginia. He probably began to think of that rugged, underpopulated region as an area through which large numbers of fugitives might be moved safely.

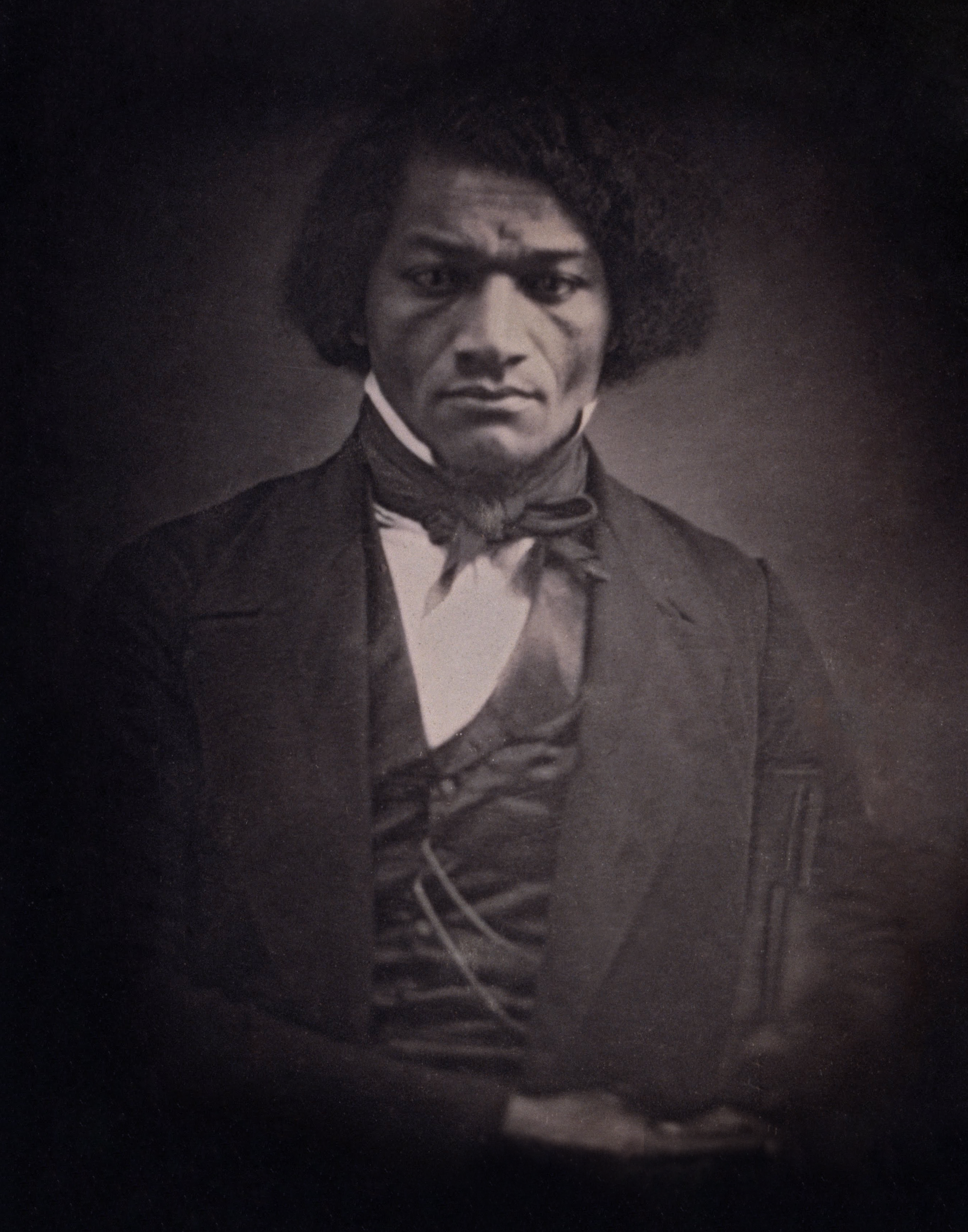

Planning with Frederick Douglas

In 1847, when Frederick Douglass met Brown for the first time, in Springfield, MA, Brown spread out a map of the United States. Pointing at the Appalachians, he told Douglass that the mountains “were placed here to aid in the emancipation of your race; they are full of natural forts, where one man for defense would be equal to a hundred for attack; they are also full of good hiding places, where a large number of men could be concealed and baffle and elude pursuit for a long time. I know these mountains well and could take a body of men into them and keep them there in spite of all the efforts of Virginia to dislodge me, and drive me out.”

THE PLAN was to start out with twenty-five picked men—almost exactly the number he had at Harper's Ferry twelve years later—who would be stationed in small cells. They would come down from the mountains to raid plantations, bring away slaves, arm them, and retreat to the mountains. Some would be guided north through the mountains to the free states—this was the literal meaning of the Subterranean Pass-Way. Others would remain with Brown. They would eventually become a bastion of armed freemen who would govern themselves in the mountains like a sovereign state.

An apocalyptic scheme

As Brown envisioned it, the plan would ultimately bring slavery to its knees. Brown was nothing if not an apocalyptic thinker—and this was an apocalyptic scheme. The South would hemorrhage slaves. Slaveholders would be impoverished, and crippled by terror. Arming blacks would generate self-respect, independence, and courage. Slavery was already a state of war, he told Douglass. Slaves had every right to fight by any means at hand to achieve their own freedom.

Douglass was taken with Brown, if not quite swayed by his plan. He thought it was impractical. Brown, he wrote, however “though a white gentleman, is in sympathy a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.”

With the privilege of hindsight, Brown's plan looks foolhardy and impossible. Was it?

Research on slave insurrections

He had done a lot of homework. Brown had studied slave insurrections like Nat Turner's. Turner had terrified the entire state of Virginia in 1831. He'd studied European guerrilla, particularly how Portuguese mountain fighters had held off the French army at the beginning of the 19th century. He'd studied the Seminole resistance to the U.S. in the swamps of Florida, in the 1830s and 1840s. He knew about the multitude of virtually independent maroon communities that runaway slaves had established in the mountains of Jamaica. And he was of course familiar with the Haitians' successful—bloody—war to overthrow French rule. He also probably knew that, since 1820, North Carolina Quakers had successfully been sending fugitives almost 1,000 miles along an underground route that ran from the Quaker enclave around Greensboro all the way to Indiana.

Great minds

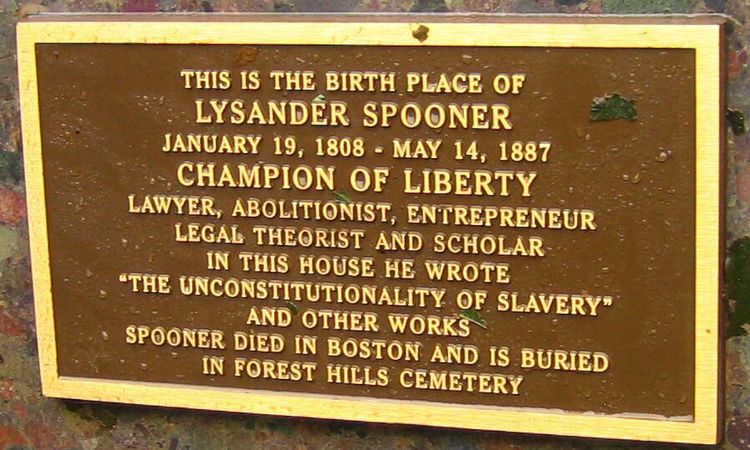

Brown's plan was not unique, by the way. An almost identical plan was advanced by a man who is almost totally forgotten today—Lysander Spooner. Spooner was a lawyer and anarchist who was well known in the 1840s for arguing that slaves had a right to wage war against their oppressors. In 1858, Spooner independently published a pamphlet urging whites to invade the South, arm slaves, and help them fight a war of liberation. He also spoke of building forts in the forest, amassing arms, and waging “a just war for liberty.” (He was also the first, I think, to assert that blacks deserved reparations for their years of enslavement.)

Many abolitionists—Arthur Tappan, even Wendell Phillips—shunned Spooner's proposals as far too dangerous, and violent. Other abolitionists' criticism reflected the widespread racist assumption that blacks had been so beaten down by slavery that they simply would not fight. Brown was of course right. Hundreds of thousands of black troops would fight valiantly in the Civil War.

When Spooner met Brown and learned about his plan, he opposed it, asserting that neither blacks nor whites in the South were ready for the kind of action that Brown intended. He thought Brown was foolhardy…that without both groups having been trained in advance and aware of the general strategy the plan was doomed to failure. (Spooner of course was right.)

BROWN WAS LIVING at this time in North Elba, New York, not far from Lake Placid. Brown had bought two hundred and forty four acres of land there, on credit from the wealthy abolitionist (and underground activist) Gerrit Smith, who hoped to establish a colony of free backs there. Brown was undeterred by the rugged boulder-strewn landscape, thickly forested with maple, oak, and spruce. They settled into a four-room farmhouse that looked out over valleys shimmering with golden rod and 4,000-foot high Whiteface Mountain. The Adirondacks, like the hands of omnipotent God, Brown believed would lift up the suffering black poor, and himself. Brown lived his beliefs. His goal was to transform the rag-tag settlement of African Americans into a self-sufficient community. He hired black workers, sowed crops, helped rationalize confused boundaries, and prepared to take the community's affairs in hand. The writer Richard Henry Dana, who encountered him there, was fascinated by this “tall, sinewy, hard-favored, clear-headed, honest-minded man,” and his teeming mob of children. Most of all, Dana was astonished to find the Browns, including even their daughters, dining with their black neighbors, addressing them as “ Mr. Jefferson” and “ Mrs. Wait,” and so on.

The Harper's Ferry raid was also the culmination of an increasingly violent decade. More and more abolitionists were beginning to think that only direct, violent action could bring the evil of slavery to an end.

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

After the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, the pacifist, Quaker style of the underground was increasingly overshadowed by men more willing to confront slavery aggressively, and to answer the violence of slavery—and federal repression—with violence. Militant abolitionist crowds physically wrenched recaptured fugitive slaves from the hands of federal officers in Boston and Syracuse. And in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania underground men—all African Americans, by the way—lured a slave master and a posse of police officers into a trap, confronted them, and shot several of them, leaving the slave master dead. West of the Appalachians, underground men in some places actually sent mounted posses of armed men across the Ohio River into Kentucky to bring out fugitive slaves who were waiting there.

Congress opens western territories to slavery; slavery divides voters

In January 1854, another act of Congress pushed still more Northerners beyond their limits of tolerance. Under pressure from the South and its allies, Congress had opened the western Territories to slavery, leaving the legality of slavery up to voters in each territory. Even many deeply racist Yankees were converted into an army of voters committed to the principle of keeping the soil of Kansas and Nebraska free for white immigrants. “[T]his Nebraska business is the great smasher in Syracuse, as elsewhere,” the Syracuse underground leader Jermain Loguen (a fugitive slave), wrote to Frederick Douglass. “It is smashing up platforms and scattering partizans at a fine rate…The people are becoming ashamed to have any connection with the ungodly course that many of their Congressmen…The time is coming when blood is to flow in this cause; and let it come I say.”

Supporting Free-Staters

When Free-State settlers in Kansas begged eastern abolitionists for guns to defend themselves, Brown's wealthy supporter Gerrit Smith promised immediate help: “Will we do for them what we can? We will!” Smith's friend, U.S. Senator William H. Seward, declared, “We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side that is stronger in numbers as it is in right.”

Editor's note: “Free-Staters” was the name given to settlers in Kansas Territory during the “Bleeding Kansas” period in the 1850s who opposed the expansion of slavery. The name derives from the term “free state”, that is, a U.S. state without slavery.

It was in Kansas that John Brown learned to fight. He arrived in Kansas in October 1855, driving a wagon loaded with rifles and swords, determined “to help defeat Satan and his legions.” Kansas transformed him from a failed businessman into a prophet whose private apocalypse would become a battle plan for guerrilla warfare.

Bristled like a lethal porcupine

In Kansas, John Brown finally found reality violent enough to fit the cosmic battle between Good and Evil he had always carried in his head. His first taste of warfare came in December 1855, when a proslavery force of two thousand men menaced the Free State bastion of Lawrence, fifty miles north of the Browns' cabins at Osawatomie. The Browns and their neighbors raced to Lawrence's defense, arriving there in a wagon that bristled like a lethal porcupine with rifles, pikes, and bayonets. Brown was commissioned a captain on the spot, and appointed to command a company of twenty men, his first military commission. From the first moment, he savored the power that weapons and leadership conferred. Although the anticipated attack never materialized, Brown had discovered that men would follow him, and fight for him.

Caution or cowardice?

STILL, UNTIL the spring of 1856, John Brown was not much different from many other scripture-quoting abolitionists in Kansas. Despite the incendiary rhetoric in the air, only six Free Staters had so far been killed. Then, in May, proslavery raiders sacked Lawrence in an orgy of burning and looting. Almost simultaneously, Kansans learned that Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the most outspoken abolitionist in the United States Senate, had been beaten senseless on the floor of the chamber by a cane-wielding Congressman from South Carolina, in a shocking tableau that left men like Brown feeling ashamed of the North's seeming helplessness in the face of Southern power. “Something must be done to show these barbarians that we, too, have rights,” Brown declared. Advised to act with caution, he retorted, “Caution, caution, sir. I am eternally tired of hearing the word caution. It is nothing but the word of cowardice.”

“Something must be done to show these barbarians that we, too, have rights,” Brown declared. Advised to act with caution, he retorted, “Caution, caution, sir. I am eternally tired of hearing the word caution. It is nothing but the word of cowardice.”

– John Brown

On the night of May 23rd, a party of men led by Brown, and including four of his sons, swept through an isolated settlement on Pottawatomie Creek, thirty miles from Osawatomie. They dragged five men out of their cabins, and hacked them to death with cutlasses embossed with the American eagle. The victims were all notorious proslavery men, and had advocated attacks against the Free Staters, but none was guilty of killing anyone. Two of Brown's sons who had not participated in the raid were so distraught that they suffered nervous breakdowns. But Brown was unrepentant.

“Only one death to die”

The murders ignited a reign of terror. Proslavery “border ruffians” raided Free Staters' homesteads. Abolitionists fought back. Federal troops scoured the prairie in search of Brown and his band. Hamlets were left desolate, farms abandoned. Osawatomie was burned to the ground. Brown's son Frederick, who had participated in the massacre, was shot dead by a proslavery man. Brown himself was almost caught in September, when a troop of dragoons rode up to the cabin where he was hiding, and stayed for refreshment. He lay hidden in the loft, with a revolver in each hand, watching through cracks in the floorboards as his host fed melons to the soldiers. Although he survived many brushes with the enemy, Brown seemed to sense his own fate. He told his son Jason, the quietest of all the Browns, a farmer who dreamed more of raising fruit trees than of vengeance, “I have only a short time to live—only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause.”

Subterranean Pass-Way

Brown's experience in Kansas gave new life to his plan for the Subterranean Pass-Way. Having eluded his enemies for months on the open prairies of Kansas, he believed that it would be to even easier to defy them in the fastnesses of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Only “a few resolute men” would be needed at first. Once they had established a chain of defensible positions, recruits could be sent down as they were needed.

Seeking “a few resolute men”

In January 1858, Brown left Kansas to find backers for his plan. His itinerary was a Cook's Tour of the leading underground figures in the East. He spent three weeks with Frederick Douglass, in Rochester, where he wrote a forty-eight article constitution for a “Provisional Government,” including a unicameral legislature, president and vice-president, supreme court, a commander-in-chief, all to serve without pay.

He told Douglass that his first objective was the capture of the Virginia town of Harper's Ferry, at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, with its federal armory and rifle works, which would provide weapons for the thousands of slaves he expected to flock to his cause.

Not long afterward, he met Harriet Tubman for the first time. Tubman was a celebrity by now within the underground. She had made eight trips to the South, and brought out some fifty fugitives. Brown recognized in her a kindred spirit, whose physical courage, boldness, and skill at traveling unnoticed through the South would be invaluable. He took to referring to her as “General Tubman,” and Tubman, for her part, embraced Brown as one of the few whites she had ever met who understood, as blacks always had, that anti-slavery work was not just moral uplift but part of a war in which combatants had to be prepared to die.

FROM ROCHESTER, Brown moved on to Gerrit Smith's mansion at Peterboro, where he was introduced to the well-connected abolitionist and educator Franklin Sanborn, for whom Brown enthusiastically sketched plans for his mountain redoubts on a scrap of paper. (Sanborn cautiously labeled the designs “woolen machinery.”) Sanborn and Brown then traveled to Boston, where Brown won the support of four more prominent radical abolitionists who had already lent their support to the Free State cause in Kansas, and now agreed to organize financing for Brown's southern strategy.

On May 8th, at a secret convention in Chatham, Brown proclaimed the establishment of his Provisional Government. Of the forty-six men present, the only whites were thirteen of Brown's followers from Kansas. Brown left Chatham with the hope that hundreds, if not thousands, of Canadian blacks would eventually join his expedition. Only one did, Osborne P. Anderson, a printer who was elected a member of Brown's provisional Congress.

To draw attention away from his real intentions, he returned to Kansas, where he lay low for the next six months. When he left Kansas in December 1858, his departure was spectacular. A Missouri slave named Jim Daniels had contacted him, and asked for help in liberating the members of his family, who were about to be sold. It was an opportunity to carry out precisely the kind of raid into slave territory that Brown had in mind, on a vaster scale, for Virginia. Brown led a detachment of men ten miles into Missouri to the plantation where Daniels lived. They collected the five members of Daniels's family, and five more slaves from another plantation nearby. A second detachment freed a slave at a third farm, and killed her owner. For the next month, the fugitives were hidden in a cabin across the state line in Kansas. In late January 1859, Brown and the twelve fugitives (a baby having been born in the interim, and christened “John Brown”), set off northward toward Nebraska with the fugitives in an ox-drawn wagon and an armed guard of fifteen abolitionists, dodging proslavery guerrillas, marshals' posses, and at one point fighting and defeating a sixty-man force of United States troops. Near Nebraska City, when thawing ice halted their flight at the Missouri River, Brown's men cut down trees and flung logs from the shore to firmer ice, and dragged their wagons across by hand, just hours ahead of their pursuers. They traveled east along an established underground route through Iowa, via Tabor and Grinnell, where they were welcomed by Josiah Grinnell, the founder of the college that bears his name. Grinnell personally reserved a boxcar for Brown's party at the nearest railhead, to carry them directly to Chicago, which they reached on March 10th. Two days later they arrived in Detroit where, presumably with the assistance of the local underground, they were taken to the wharf and ferried across the Detroit River to Windsor. As he watched them embark, Brown recalled a passage of Scripture: “Lord, now lettest thy servant depart in peace, for my eyes have seen thy salvation.”

They had covered almost fifteen hundred miles in eighty-two days, proof to scoffers, Brown felt sure, that he was capable of making the Subterranean Pass-Way a reality.

Harper's Ferry history

AROUND TEN THIRTY on the dank night of Sunday, September 17th 1859, seventeen shadowy figures led by the man some now called Old Osawatomie slipped down from the brooding bluffs of Maryland overlooking the Potomac River, and with the brisk steps of men who knew that whatever the outcome they were about to make history, they entered the black tunnel of the covered railroad bridge that spanned the river to Harper's Ferry. Each carried a Sharpes rifle, a brace of pistols, and a knife sheathed at his waist. Twelve of the men were white, five black. Almost all were in the twenties. Some were naive idealists, others veterans of the guerrilla war in Kansas. Among them were Brown's youngest sons Watson and Oliver, two neighbors from North Elba, New York, a Canadian spiritualist, a black graduate of Oberlin College, a pair of Quakers who had abandoned their pacifist beliefs to follow Brown from Iowa, a freed slave hoping to liberate his wife and children, and boys from Maine, Pennsylvania, and Indiana.

We all know the rest of the story. Measured against Brown's hopes, the raid was a spectacular failure.

1850s South

Brown failed to take account of the real nature of the South in the 1850s. There was little organized underground activity south of the border states. (The main exception had been the Quaker counties of North Carolina, but underground work there apparently ceased to function after about 1853, when the last known underground men were forced to flee.)

Brown did no investigation whatever of the realities that his plan would have to deal with in the South. So strongly did he feel that he was guided by God, and so intensely did he identify with enslaved African-Americans that he failed to take WHITE Southerners into account. Of course, in the mid-19th century no one did focus groups, or market research, so to speak. Brown lived in an age that believed that faith and destiny could trump reality.

The South was, in effect, what we call today a totalitarian society. I'm using that word deliberately. Yes, it's an anachronism, a 20th century term. But it accurately describes what the South was like for African-Americans both enslaved and free—and for whites who dared to publicly challenge the institution of slavery. For them, the Bill of Rights simply did not apply: there was no right of free speech, free press, or free assembly. Whites who dared were smeared, attacked, ostracized, driven from their homes, and sometimes killed. This had been going on for decades. By the 1850s the kind of whites whom Brown counted on to help him in the Deep South had fled the region. Nearly all the antislavery Quakers in North Carolina had migrated north, or fallen silent. Those who remained were silent and cowed.

Harper's Ferry was, ultimately, a success

But as a spark that lit a feverish passion for freedom in the hearts of both white and black abolitionists, the raid was a spectacular success. Less than two years after Brown's execution in Charlestown, Virginia, war came. As Union armies marched southward, John Brown's failed dream of a Subterranean Pass-Way became a great highway. Wherever the armies marched, slaves poured off the plantations, to the Union lines, and to freedom.

About the Author

FERGUS M. BORDEWICH is the author of eight non-fiction books: CONGRESS AT WAR: How Republican Reformers Fought The Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, And Remade America, (Alfred A. Knopf, 2020); THE FIRST CONGRESS: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (Simon & Schuster, 2016. Winner of the 2019 D.B. Hardeman Prize), AMERICA'S GREAT DEBATE: Henry Clay, Stephen A. Douglas, and the Compromise that Preserved the Union (Simon & Schuster, 2012. Winner of the 2012 Los Angeles Times History Prize); WASHINGTON: The Making of the American Capital (Amistad/HarperCollins, 2008); BOUND FOR CANAAN: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (Amistad/HarperCollins, 2005); MY MOTHER'S GHOST, a memoir (Doubleday, 2001); KILLING THE WHITE MAN'S INDIAN: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century (Doubleday, 1996); and CATHAY: A Journey in Search of Old China (Prentice Hall Press, 1991). He lives in San Francisco, CA with his wife, Jean Parvin Bordewich.

Congress at War tells the story of how Congress helped win the Civil War–a new perspective that puts the House and Senate, rather than Lincoln, at the center of the conflict. This brilliantly argued new perspective on the Civil War overturns the popular conception that Abraham Lincoln single-handedly led the Union to victory and gives us a vivid account of the essential role Congress played in winning the war.

Building a riveting narrative around four influential members of Congress–Thaddeus Stevens, Pitt Fessenden, Ben Wade, and the pro-slavery Clement Vallandigham–Fergus Bordewich shows us how a newly empowered Republican party shaped one of the most dynamic and consequential periods in American history. From reinventing the nation's financial system to pushing President Lincoln to emancipate the slaves to the planning for Reconstruction, Congress undertook drastic measures to defeat the Confederacy, in the process laying the foundation for a strong central government that came fully into being in the twentieth century. Brimming with drama and outsized characters, Congress at War is also one of the most original books about the Civil War to appear in years and will change the way we understand the conflict.

Bordewich's last book, The First Congress, tells the astonishing story of the most productive Congress in American history. When the members of the First Congress met in New York, in 1789, the new nation was still fragile, riven by sectional differences, hobbled by competing currencies, crushed by debt, and stitched together only tentatively by the new Constitution. The Constitution provided a set of principles but offered few instructions about how the government should operate, leaving it to Congress and the president to create the machinery of government. As James Madison put it, “We are in a wilderness without a single footstep to guide us.” Had Congress failed in its work, the United States as we know it might not exist. Along with Madison, powerful men such as Roger Sherman, Oliver Ellsworth, Elbridge Gerry, and Robert Morris often clashed, sometimes savagely, but ultimately they forged a consensus that gave strength and credibility to the new government. Bordewich brings alive the passions and conflicts of these extraordinary men, who, along with President George Washington and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, breathed life into the Constitution. Bordewich immerses us in the dramatic debates over the Bill of Rights, the creation of the president's cabinet, the adoption of a new capitalist financial system, and the acrimonious argument over the new capital, among many other issues. Some of the issues the First Congress faced still challenge us: literal versus liberal interpretations of the Constitution, conflict between states rights and federal power, protection of individual rights, and more. How Congress and the president achieved as much as they did is a story that could not be more timely in our era of hyperpartisanship and governmental gridlock.

America's Great Debate, told the epic story of the nation's westward expansion, slavery and the Compromise of 1850, centering on the dramatic congressional debate of 1849-1850—the longest in American history—when a gallery of extraordinary men including Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Stephen A. Douglas, Jefferson Davis, William H. Seward, and others, fought to shape, and in the case of some to undermine, the future course of the Union.

In April 2013, America's Great Debate was named the Best History Book of 2012 by the Los Angeles Times. Citing the book's “page-turning detail,” the Times's citation read, in part: “Wise and witty in equal measure, the book dusts off the marble busts to find the humanity in the ambition of Henry Clay, the industry of Stephen A. Douglas, and the ardor of Jefferson Davis and John Calhoun. Bordewich's vivid prose allows us to smell the cigar smoke, taste the whiskey, and feel the mud on the boots as statesmen, time servers and true believers jostle against the growing threat of disunion and war.” In 2013, America's Great Debate was also highlighted at the National Festival of the Book, in Washington, D.C.

America's Great Debate was also named one of the Best Books of 2012 by the Washington Post. In his review, Post publisher Donald E. Graham called the book “original in concept, stylish in execution. [It] provides everything history readers want. Two things above all: a compelling story and a cast of characters who come convincingly to life.”

Bound for Canaan was selected as one of the American Booksellers Association's “ten best nonfiction books” in 2005; as the Great Lakes Booksellers' Association's “best non-fiction book” of 2005; as one of the Austin Public Library's Best Non-Fiction books of 2005; and as one of the New York Public Library's “ten books to remember” in 2005.

Washington a history of the byzantine politics behind the founding of the nation's capital and slaves who built it, was named by Jonathan Yardley of the Washington Post as one of his “Best Books” of that year.

Bordewich is a frequent book reviewer for the Wall Street Journal and other popular and scholarly periodicals, mostly on subjects in 18th and 19th century American history. He has published an illustrated children's book, Peach Blossom Spring (Simon & Schuster, 1994), and wrote the script for a PBS documentary about Thomas Jefferson, Mr. Jefferson's University. He also edited an illustrated book of eyewitness accounts of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre, Children of the Dragon (Macmillan, 1990).

He has been an independent historian and writer since the early 1970s. In 2015, he served as chairman of the awards committee for the Frederick Douglass Book Prize, given by the Gilder-Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, at Yale University. He is a frequent public speaker at universities and other forums, as well as on radio and television. His articles have appeared in many magazines and newspapers, including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, American Heritage, Atlantic, Harper's, New York Magazine, GEO, Reader's Digest, and others. As a journalist, he traveled extensively in Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa, writing on politics, economic issues, culture, and history, on subjects ranging from the civil war in Burma, religious repression in China, Islamic fundamentalism, German reunification, the Irish economy, Kenya's population crisis, among many others. He also served for brief periods as an editor and writer for the Tehran Journal in Iran, in 1972-1973, a press officer for the United Nations, in 1980-1982, and an advisor to the New China News Agency in Beijing, in 1982-1983, when that agency was embarking on its effort to switch from a propaganda model to a western-style journalistic one.

Bordewich was born in New York City in 1947, and grew up in Yonkers, New York. While growing up, he often traveled to Indian reservations around the United States with his mother, LaVerne Madigan Bordewich, the executive director of the Association on American Indian Affairs, then the only independent advocacy organization for Native Americans. This early experience helped to shape his lifelong preoccupation with American history, the settlement of the continent, and issues of race, and political power. He holds degrees from the City College of New York and Columbia University. In the late 1960s, he did voter registration for the NAACP in the still-segregated South; he also worked as a roustabout in Alaska's Arctic oil fields, a taxi driver in New York City, and a deckhand on a Norwegian freighter.

Bordewich is represented by Adam Eaglin, who may be contacted at: Elyse Cheney Literary Associates, 78 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 Tel: (212) 277-8007 | email: [email protected]

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

Fair Use Notice: The PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault is dedicated to advancing understanding of various social justice issues, including human trafficking and related topics. Some of the material presented on this website may contain copyrighted material, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to promote education and awareness of these important issues. There is no other central database we are aware of, so we put this together for both historical and research purposes. Articles are categorized and tagged for ease of use. We believe that this constitutes a ‘fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information on fair use, please visit: “17 U.S. Code § 107 – Limitations on exclusive rights” on Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.

EYES ON TRAFFICKING

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.