Was that made by Arizona prison labor? Prisoners make many everyday items

Your child is sleeping on a mattress made from prisoners' clothes.

At state universities, the bedding used in your kids' dorm rooms comes from T-shirts and other clothing confiscated from prisoners during quarterly “contraband searches.” If a prisoner has too many T-shirts (they're allowed just a few), or if the “D.O.C.” screenprint wears off, it's considered contraband. Corrections officers take the clothes and force people to buy new ones. Few people get replacements.

On paper, the mattresses are made from recycled denim that is then stitched together by workers inside the prison's sewing facilities. But a handful of prisoners who worked in the recycling plants said it's more than just denim — their stolen clothes are also turned into a slurry, and then into foam bedding. Internal emails from Department of Corrections officials also revealed that the foam in mattresses are made from prisoners' clothes.

Bookcases, ottomans, recliners, benches and chairs in dorm rooms are also manufactured and reupholstered by prisoners. And while the cost of sleeping in one of these prison-furnished rooms can range anywhere from $3,000 per student to upward of $11,000 per year, the cost to make the product is minuscule. Prisoners stitch the beds together or refurbish other furniture for a minimum wage of 71 cents per hour, according to pay records obtained by The Arizona Republic from sources at the Department of Corrections.

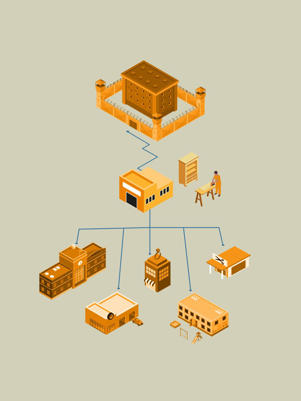

But it's not just dorm rooms where prison labor shows up unexpectedly.

The city or town you live in may hire prisoners to clean neighborhood streets. They do grounds maintenance at your local country clubs or city-owned golf courses.

They even work for the Special Olympics and help set up for the state fair.

The public school in your district may use prisoners to avoid paying benefits or salaries to janitorial staff, but that work requires them to remain hidden from view and not walk into rooms occupied by students or staff.

Prisoners clean the grounds at the state's most popular country music festival. They build the frames that support homes. They package the salads that may be in your fridge and build the cabinets in your luxury apartment complex.

But most Arizonans would never know it.

For the past decade, prison labor has been a growing source of cheap, reliable labor for dozens of businesses, hundreds of government agencies, and thousands of individuals. But companies and the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation & Reentry have made sure to keep talk of these goods and the labor that makes them relatively out of the public's knowledge. Some companies that employ prisoners have them sign gag orders denying them the right to discuss details of their work. And the Corrections Department doesn't allow companies to speak freely about their use of the labor, which many get at a discounted rate from the typical market wage.

Saving on the cost of labor is one reason companies say they sign on, but they are also looking for workers who will show up every day no matter how tedious, grueling or dangerous the job. The fact that workers end up earning far less than the minimum wage and do jobs that few in the free market would want to do is not something many companies want to share with the general public. So they'll tell you how the jobs benefit the prisoners, and how they provide skills prisoners can use to secure jobs when they get out.

Some companies that hire prison labor or buy the products prisoners create believe this. But they know nothing about the ongoing hazards that prison workers face, such as losing the use of body parts or crushing entire limbs without workplace protections, and how they are then treated by some of the state's most notoriously bad health care providers.

“I really love the fact that, you know, it gives them just another leg up when they are paroled to come back,” said Matt Fulton, the owner of the Whining Pig restaurants, who used prisoners to create booths and install them at two of downtown Phoenix's trendy nightspots, Rough Rider and Pigtails. ”I think it's such an amazing program.”

But workers in the shops that created booths at Fulton's two businesses have told The Arizona Republic about instances of untreated injuries, being forced to work without proper safety gear, and threats about what will happen if they ever take breaks. When asked if he's ever inquired about work conditions, Fulton said he hadn't. He said he's been to the workshops and didn't notice any problems, but “if I was made aware of it, and if I was thinking about it, yeah, that would be nerve-wracking.”

When corrections officials market the opportunity as a benefit to prisoners, they mislead or omit details to business owners and managers about the hidden fees and costs that prisoners get deducted from their already-low pay. On the Arizona Correctional Industries website, for example, the company said that prisoners' pay is so low because they don't have the typical costs associated with living like people on the outside have, such as rent, food, or medical costs.

Larry Williams, a sales and marketing manager with Waste Connections of Arizona, was under the assumption that prisoners don't pay for their room and board, and that the prisoner wages he agreed to with Arizona Correctional Industries went directly to either workers' savings or their own pockets.

In reality, out of the $12.80 he pays ACI per hour through their minimum wage surcharge, the prisoners only make $3.25 an hour. ACI pockets the rest. But that's before the department takes money from prisoners for their utilities, 30% for prisoners' rent, and other various fees.

In the end, prisoners receive little more than 50 cents an hour to spend. The rest goes into a retention, or trust, account that some have said they never saw again. (The Department of Corrections denied multiple requests from The Arizona Republic to review those accounts for discrepancies.)

Another business owner, Randy Rogers, used prisoners to help craft wooden parts for his furniture store, Olde Mercantile, in Gilbert. He was told that ACI paid their prisoners well above minimum wage. “They said that they paid these guys a prevailing wage of, like, 14 or 15 bucks an hour,” he said, shocked to learn that in reality they received less than $1 before deductions.

For those who are aware, silence is usually the best way to deal with the fact that their products are being made behind the scenes and inside of prisons. The less said, the better.

Shane Co., a well-known local jewelry store, hired Modern Millwork to make the cabinets and countertops for one of its stores in the Phoenix area. But Modern Millwork never told Shane Co. that the cabinets and countertops were actually built by prisoners at ACI.

In an email to an ACI salesperson from July last year, Mark McClenney, the owner of Modern Millwork, needed pictures taken of the products being made for his client. But he insisted that the photos hide any clues that prisoners were used for construction.

“We are billing Shane Co. and they want some progress pictures for their records,” McClenney wrote in the email. “As usual, our client thinks these are being made in our shop, hence the nondescript and discreet.”

Shane Co. executives could not be reached for comment on their contract with Modern Millwork.

But Modern Millwork did the same with at least five other clients, based on quotes and invoices obtained by The Republic and KJZZ News. These customers included an elementary school, a day care center, a beauty parlor, a bowling alley and a discount tire store.

Modern Millwork would not comment when asked if it hid its use of exploited labor from Shane Co.

Many companies exploit prison labor while also having strict rules about not hiring people with felony records, as Swift Trucking does. When asked why the company uses prisoners to refurbish, detail, and fix long-haul trucks, a human resources representative denied using prisoners and said adamantly that, “We do not hire felons.”

But a contract with Common Market Equipment Company, which owns Swift Trucking, is on file as recently as 2018.

And at least one prisoner has tried suing the company for being injured on the job while climbing on top of a truck to clean it using a “homemade ladder,” according to the lawsuit.

Swift Trucking would not comment on the lawsuit, which is still pending in Maricopa County.

For companies that boast their use of prison labor — such as Hickman's Family Farms — prisoners say that the rosy image of the employer-worker relationship doesn't reflect their experiences. Some say they work under sweatshop-like conditions and are immediately replaced when injured or sick.

Hickman's does, indeed, hire prisoners once released from prison. They can live at the worksite in company-owned housing for a year, and receive half of their yearly rent back at the end, according to the company's website. That's about $2-3,000.

But the job is not enjoyable, even for civilian farmworkers, who often leave the job after just a few days. One of the men who worked at Hickman's while incarcerated said people on the outside sometimes come in for work, but don't last even a few days. An email sent to the Hickman's owners on work conditions, as well as multiple phone calls, went unanswered.

“Having the ability to work at all is a definite plus, but the money that you make is near slave wages,” said Jamie Dhaene, a former prisoner who was serving time for a DUI and worked at Hickman's for two weeks, but then quit and was forced to work in groundskeeping.

And for all those eggs being served on your table? The savings passed on to the consumer is borne by the prisoners at the farm: “The environment is grotesque,” Dhaene said. “The living conditions are as close to inhumane as possible.”

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Was that made by Arizona prison labor? Prisoners make many everyday items

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

Fair Use Notice: The PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault is dedicated to advancing understanding of various social justice issues, including human trafficking and related topics. Some of the material presented on this website may contain copyrighted material, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to promote education and awareness of these important issues. There is no other central database we are aware of, so we put this together for both historical and research purposes. Articles are categorized and tagged for ease of use. We believe that this constitutes a ‘fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information on fair use, please visit: “17 U.S. Code § 107 – Limitations on exclusive rights” on Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.

EYES ON TRAFFICKING

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.