'We'll help you': Human trafficking protocol to ensure every victim's need is met

Had police asked Alexandra Stevenson who controlled her money while she was with her ex-boyfriend in 2007, a switch may have clicked.

Had they asked how she decided what to wear every day or if her boyfriend tracks her cellphone, maybe it would have planted a seed of doubt in her relationship.

Had they asked those questions, maybe it wouldn't have taken 10 years for her to realize that she was being trafficked by the person she thought was her partner.

“It was labelled by both myself, and the police, as domestic violence, and I certainly thought of it all as my own bad decisions,” Stevenson told the Whig-Standard from Kamloops, B.C. “I had been complicit in exploitation, I had thought it was, you know. I was an empowered sexually liberated woman, and this was a good idea until it wasn't, and then I was trapped.”

It wasn't until 2017, while telling her story of what she thought was domestic violence to a person working in anti-trafficking that she learned she'd actually been trafficked herself.

So, when she was asked to peer-review the Human Trafficking Protocol for the City of Kingston and Frontenac County and provide feedback, she wanted to make sure that anyone who was brave enough to disclose their experiences wouldn't find themselves in her shoes.

“I fell through the cracks,” Stevenson said. “I'm not pointing fingers; I'm not blaming the police. They didn't have all the information, and I didn't provide it to them, but they also didn't ask the right questions.”

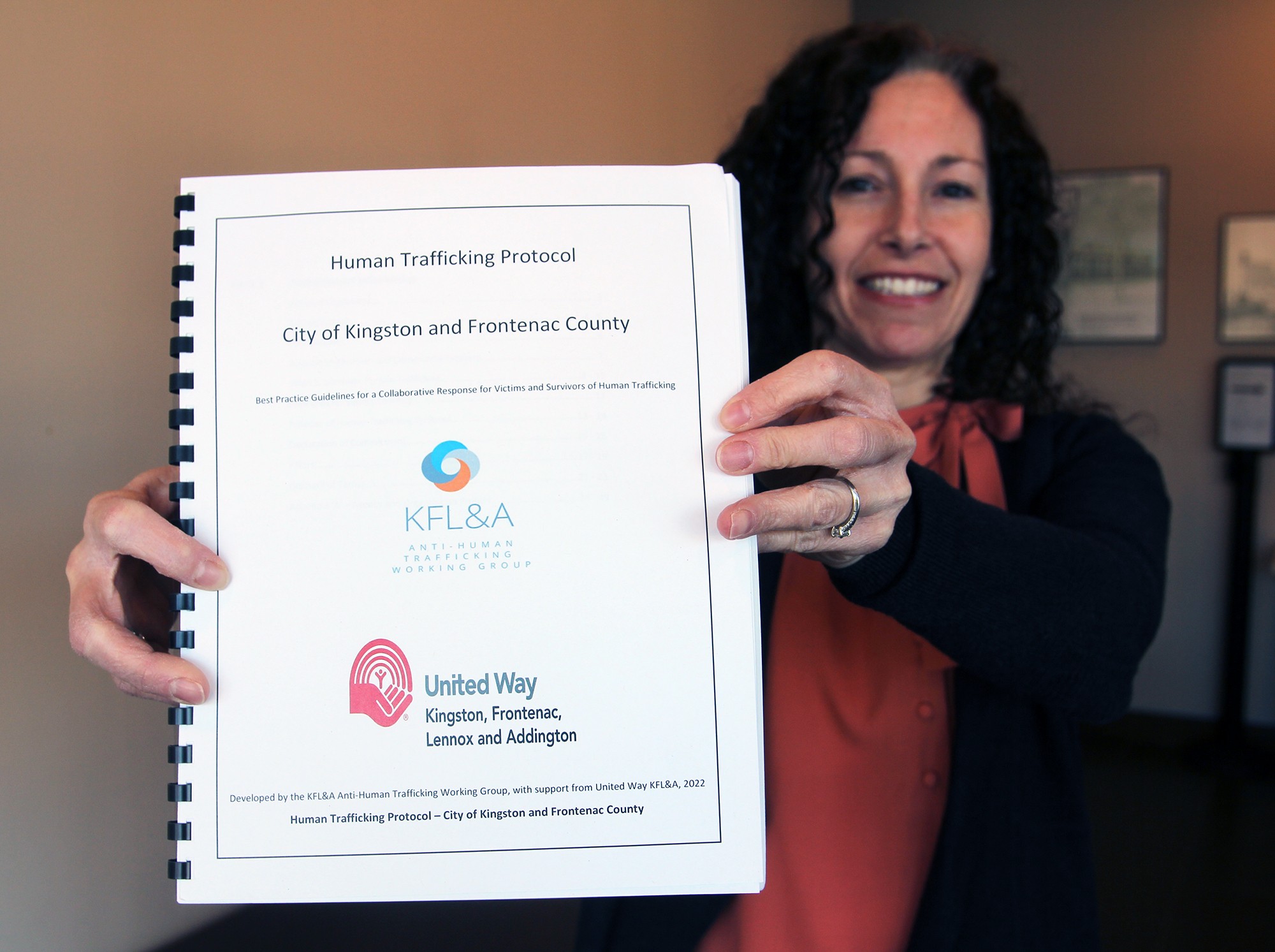

The new protocol, which will evolve over time, was officially unveiled on March 7 at Kingston City Hall, but Lana Saunders, chair of the Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox and Addington Anti-Human Trafficking Working Group, said it has been in the works for more than a year and she only wants it to grow.

“The purpose of the (working) group is to build partnerships with community agencies to combat human trafficking. What better way than to have a protocol?” Saunders said Wednesday morning within the office of Victim Services of Kingston and Frontenac, located at Kingston Police Headquarters on Division Street.

“Everyone can refer to the document and have best practices, avoid gaps in services, avoid duplication of services, just have a one-stop shop.”

According to a December 2022 report from Statistics Canada, there were 3,541 police-reported incidents of human trafficking in Canada between 2011 and 2021, and 2,688 victims were identified. Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan and Ontario were higher than the national rate.

“The relatively high number of incidents in Ontario may be attributed to the concentration of urban areas in the province,” the report states. “Such population centres may form part of human trafficking corridors, used by traffickers to increase profits, avoid detection and isolate victims through psychological control.”

The protocol, which is focused on those being exploited sexually and for their labour, is a set of best-practice guidelines for a collaborative response to human trafficking by breaking down barriers for those who have escaped it. The protocol was entirely funded by the United Way of Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox and Addington.

The agencies that have signed the protocol have agreed to help lead efforts in preventing trafficking, educate those who may be vulnerable to trafficking, respond to trafficking incidents, support those who have escaped by working together, co-ordinate collective response and resources, and implement information-sharing agreements.

The three pillars of the protocol are: prevention, education and awareness; identification of trafficking victims; and intervention, assessment and support.

“We'll see how well it does,” Saunders said, cautiously optimistic. “It is just brand new. We'll see how people use it.”

Those who have signed the protocol include Kingston Police, Kingston Interval House, Limestone District School Board, Youth Diversion and many others. Saunders would like more agencies to sign the protocol as well.

She said having Stevenson review the protocol document was essential to ensure they approached it through a victim, survivor, trauma-informed lens.

“The more insight we have into those experiences, and the trauma, the better we can help,” Saunders said.

One of the more important aspects of the protocol is ensuring those leaving trafficking have safe and secure housing with support when they need it. Saunders explained that when she encounters a victim or survivor, she is generally one of the first people on the scene of the crisis and finding shelter is essential.

It isn't as simple as putting a victim alone in a hotel room, because that is usually the setting of trafficking operations, and they often need support readily available throughout the day or night. Saunders said that with the protocol, she'll know her sure options more readily.

She described that if, their trafficker is providing them with the basic necessities of at least one meal a day, maybe some money but definitely not all of it, and a roof over their head. If a person has just fled that situation, usually with just a bag of possessions, and services can't provide that and then some, why would they leave?

“We're encouraging all these people to come forward. We'll help you, there's support, we're going to believe you, all you have to do is reach out for help. But if we can't help them at the moment, then we haven't done what we've said we're going to do,” Saunders said. “If we're encouraging people to come forward, we better be ready to support them when we do.”

Stevenson explained that the protocol should ensure that if a person comes forward to one agency, they will either be able to access help there or the agency will immediately get them to one of the protocol partners.

When Stevenson went to a domestic violence shelter, even volunteering at one, the people working there were great, but everything they offered didn't seem to fit her situation. It was domestic violence, but it was more than that. She said she was angry that she was hit, but she was angrier that she feared for her life and she couldn't explain why.

“I couldn't explain why I thought it was a good idea to take off my clothes until it wasn't, but why did I keep doing it?” Stevenson said. “I didn't understand that, and a lot of that is so entrenched in trafficking, in the mindset, and the mind control and trauma-bonding that happens in trafficking.

“Not only did I fall through the cracks from a law enforcement perspective, but I fell through the cracks from a healing perspective and a self-identification perspective.”

Send us opinions, comments and other feedback. Letters may be emailed to [email protected].

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.

EYES ON TRAFFICKING

This “Eyes on Trafficking” story is reprinted from its original online location.

ABOUT PBJ LEARNING

PBJ Learning is a leading provider of online human trafficking training, focusing on awareness and prevention education. Their interactive Human Trafficking Essentials online course is used worldwide to educate professionals and individuals how to recognize human trafficking and how to respond to potential victims. Learn on any web browser (even your mobile phone) at any time.

More stories like this can be found in your PBJ Learning Knowledge Vault.