The Problem of Statistics in Human Trafficking and the Average Age of Entry into Sex Trafficking

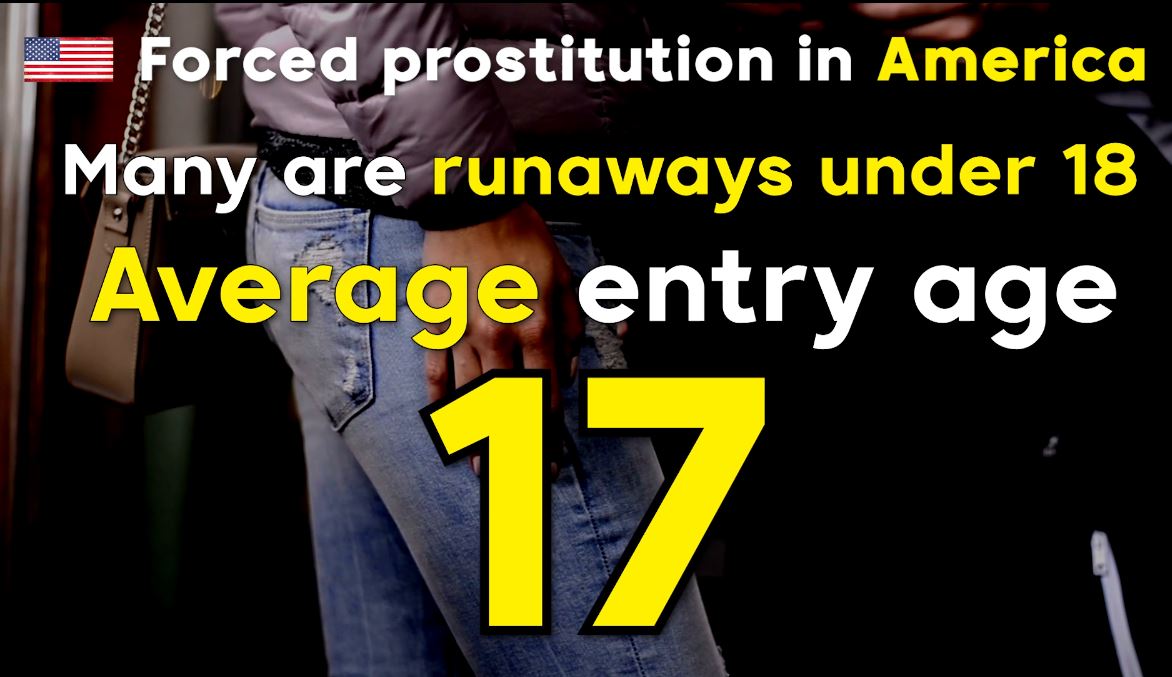

Editor's note: Our Human Trafficking Essentials course promotes the average age of entry into sex trafficking as 17, based upon the below research. The below makes clear there are no studies that demonstrate that age in a truly measurable manner.

Our materials make clear that the statistics in the human trafficking field are difficult to gather AND those that collect those statistics (whether a nonprofit, NGO, government agency, university, etc.) have their own reasons for providing the results they present.

We alter our courses when new data is made available, so if you know of a new study, please reach out through our contact page and we will update our educational materials.

“Facts are stubborn, but statistics are more pliable.” – Mark Twain

Much as experts on the phenomenon of human trafficking are both everywhere and nowhere to be found at once, with many who simply have no idea what they're talking about often being heralded as renown legends of child safety and heroic liberators of trafficked women from pimps and slavers, there are similarly a lot of nonsense statistics thrown around when it comes to such matters.

Let's examine one of these common but nonsensical statistics often used to bring attention to the issues of human trafficking and child exploitation, and much more specifically and often, to fundraise off them. Up for examination is the oft-cited claim that there are 100,000 to 150,000 people, many of them children, being held as commercial sex slaves in the United States alone. This is a rather shocking statistic, and it's no surprise that it's so frequently used to illustrate the scope of the problem. Yet, it originates from two very shaky, if not outright false, other statistics.

First is the claim that over 2,000 children go missing every day, or approximately over 800,000 every year – a frequent talking point among politicians and child safety advocates alike. Yet, it is a completely bogus and inflated number. There is a kernel of truth in this number, and that comes from the number of reports law enforcement files regarding a runaway child every year. Yet here's the kicker – if a single child runs away more than once, each run away attempt gets its own separate report, even though it's for the same child. If two or more jurisdictions are involved, each jurisdiction files its own report.

If a single child runs away 20 separate times, 20 separate reports will be filed for that one (1) child (LaCapria, 2020). If the case involves two jurisdictions, such as if the child crosses the border into another township, those 20 reports become 40 reports. Suddenly, the 800,000 number just doesn't seem all that intimidating. Yet, we find ourselves facing another kicker: no one actually knows where the 800,000 number actually originated from, as it's double the average number of just over 400,000 reports for each year of 2018, 2019, and 2020. This number is further rendered wildly inaccurate to rely upon given that the overwhelming vast majority of children who run away are found and returned to their homes.

Yet, there is a second, equally problematic part to the claim of 100-150,000 commercial sex slaves in America. This appears to be claim that “one in six runaways are targeted by human traffickers.” This is not so much a false statement as much as it is taken out of context: this number comes from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) which stated that, “Of the nearly 26,300 runaways reported to NCMEC in 2019, 1 in 6 were likely victims of child sex trafficking” (LaCapria, 2020). It is vitally important to note that NCMEC did not state whether these likely child sex trafficking victims became victims of child sex trafficking after they ran away or that they ran away in the first place because they were victims of child sex trafficking. However, the popularized version of the “one in six” claim does make the assumption that they were only targeted by traffickers after they ran way. Similarly, when we look at the numbers here, we see that the 26,300 runaways reported to NCMEC is less than 3.3% of the claimed 800,000 number examined above.

However, this is the interesting part: if you erroneously combine these two statistics, one in six (0.167) runaways being targeted by traffickers by the 800,000 children who go missing every year, you miraculously get the 100-150,000 number of “commercial sex slaves in the United States.” Specifically, 0.167 x 800,000 = 133,333.

In short, someone who didn't understand nuance and context did some elementary math and was careless with their statistics, and now we're dealing with a massive misinformation problem. This is, in fact, a well-documented problem, with scientists for decades having bemoaned journalists who take one specific finding in a study that applies very narrowly, only to have it reported as a miracle cure for an entire population. Thus, it shouldn't surprise us to find this in the anti-trafficking world, but it remains nonetheless remarkably counterproductive to efforts to eradicate modern slavery.

Besides faulty math and people taking very specific numbers relevant to a tiny population and applying them to all human trafficking cases the world over, the problem is further complicated by the hidden nature of human trafficking. This makes the phenomenon incredibly difficult to study, as trafficking is a highly clandestine crime, poorly understood by even the best scholars, and many victims of trafficking simply do not know that they are victims. Additionally, gaining access to the most vulnerable populations to accurately measure their rates of victimization is hard, as they are often fearful of attracting the attention of law enforcement or others whom they perceive as capable of doing them harm. These populations are often among the most marginalized in society, and as such have reason to be concerned about further victimization from those they perceive to be outsiders.

Then, there are methodological issues in how to measure it. How are victims supposed to report in a self-report questionnaire that they're victims of a crime when they don't know enough about the nature of trafficking to know that they're victims? How does a researcher even objectively measure something like that in a scientific survey? Self-reports are, quite notoriously, problematic in the sciences and prone to individual bias and limitations, while subjects can be deceptive in otherwise time-consuming and costly interviews. Likewise, privacy laws prevent researchers from collecting certain information that would be immensely useful in identifying trends in this area.

Further, cultural deviations in understandings of “choice” and agency muddy the waters even more. Victims may be under the illusion that they are in a trafficking situation by their own will due to cultural context surrounding notions of free will and choice. Often, foreign victims of labor trafficking will state that they chose to be in such horrid conditions to investigators and first responders. This is a dangerous situation as first responders may not understand the cultural context surrounding these notions and believe that the victims are using an Americanized / Western concept of choice when in fact they are not – assuming all is well and dismissing claims of trafficking. Only further, culturally informed questioning reveals that they have been compelled into servitude through force, fraud, or coercion (Cianciarulo, 2007).

The lesson for the reader up to this point is simple: when it comes to statistics in human trafficking, one must always engage in a little detective work. At the minimum, this means always checking the source of the statistic and comparing them to the larger picture alongside other, much more trustworthy and verified statistics. Never accept a number in this field at face value, and seriously question those who rely upon them or offer them up definitively as potential charlatans, not professionals.

The widespread implications of the lack of merit behind many of the statistics relied upon for our understanding and awareness raising of child safety and human trafficking cannot be overstated. If those dedicated to eradicating human trafficking, a very real and very serious issue, use such misinformed numbers that are readily defeated by mere high school algebra, then there is a very real danger that nothing else they have to say will be taken seriously by the public: it will all be dismissed as fearmongering over a problem that doesn't actually exist. Moreover, we cannot fight what we do not understand, and if we are wasting our time fighting mere illusions of the problem then no victims are getting helped.

This brings us to the issue of the average age of entry into sex trafficking. A vast number of anti-trafficking organizations are increasingly stating that the age of entry into sex trafficking is 12-14 years old (Shared Hope International in particular commits further crimes against mathematics by splitting the difference here and calling it 13 years old). Accompanying this claim is that 244,000-300,000 children are at risk for commercial sexual exploitation, in addition to 105,000 children already being commercially sexually exploited.

This is, in a word, appalling. Yet, the astute reader is wise to note the overlap between the latter of these claims and the claim of 100-150,000 existing in commercial sexual slavery. Indeed, something very fishy is going on with these numbers, to the point that when reporters inquired with organizations as to where they get these numbers, their inquiries are often stonewalled or outright ignored (Har, 2013): which as I mentioned previously is not a very good look for a movement as a whole.

These numbers come from a single study: Estes and Weiner, 2001. Let me state the obvious here first: anyone who knows anything about science knows that a single study does not science make. Science comes about through a consensus of findings. In this instance, there is no consensus: there is only the single study that is accepted at face value. To make matters worse, another 2006 study (Edwards et al., 2006) took the findings in Estes and Weiner and further extrapolated that 650,000 children were at risk of sex trafficking nationwide.

The critical error that was made here is identical to the example of 100-150,000 commercial sex slaves in the United States: the numbers used to arrive at these alarming statistics regarding child commercial sexual exploitation were applicable only to the study's sample population, not the overall sex trafficked population as a whole (Hall, 2015).

Indeed, here the error was much worse: a single paragraph describing the sample population was taken out of context and erroneously applied to the entire population of the United States (reference Estes and Warner, 2001, p. 92).

Moreover, the conclusion that the average age of entry into sex trafficking is 12 to 14 is easily falsifiable by considering the very word “average.” One finds the average by taking the sum of the terms divided by the number of the terms. Simply put, half of the values are going to be lower than the average, and half are going to be higher. If the average age of entry into sex trafficking was indeed age 12 to 14, then we'd see more two- and five-year-olds entering prostitution and being sex trafficked that we actually do. Thus, just by basic elementary school math we can tell that this claim is false.

To further impeach this notion, one must consider that if a youth is being sex trafficked, then they began being sex trafficked at a younger age by definition. For instance, if one is being sex trafficked at age 16, then they obviously entered sex trafficking at a age younger than 16. If one is being sex trafficked at age 30, then one obviously entered sex trafficking at an age younger than 30, but not necessarily younger than 16. This reveals another problem with relying on Estes and Warner, 2001's data: Estes and Warner were only interested in sex trafficking among minors, so they only sampled those under the age of 18. By specifically sampling and only counting those under 18 in one's sample, the estimated age of entry is artificially lowered if that age is then later used to represent the age of entry for all sex trafficking victims, not just those trafficked as minors.

And yet, even this is not the end of this matter. The study in question only examined domestic sex trafficking victims (much more specifically, domestic minor sex trafficking victims) not foreign national sex trafficking victims. Later studies and data which took a more holistic view and samples revealed the average age of entry for domestic victims of sex trafficking to be 19 years old (Cunningham & Jacquin, 2018; Polaris, 2019a). This is a remarkably similar finding to those around the world for domestic victims of sex trafficking within their home countries (Lyon, 2014). Studies examining the average age of entry for the entire population, both domestic and foreign national victims of sex trafficking in the United States, reveal the average age to be 17 years old (Polaris, 2019).

This whole ordeal once again demonstrates the importance of knowing how to properly read a scientific study and not present what applies to a small percentage of the population as representative of the whole, to the point that Dr. Estes of Estes and Warner, 2001 fame had to even come out and decry the misinterpretation of his study personally, going one step further in stating that the world of the 1990s in which he conducted this research is not the world of today, and thus, his research is no longer applicable (Kessler, 2015). Nonetheless, anti-trafficking organizations across the world continue to tout the 12 to 14 number as the age of entry into sex trafficking.

One would be forgiven, then for assuming that the matter is settled: after all, studies have revealed that the average age of entry into sex trafficking, regardless of one's immigration status, in the United States is 17 years old. Unfortunately, like everything else in this field, it's not so cut and dry.

The harsh reality is that we don't even have enough data to try to make an informed estimate about the age of entry into sex trafficking. For one, the problem is simply that massive. Secondly, of perhaps the most comprehensive dataset we have on the issue, only 4% of sex trafficking victims reported their age of entry into sex trafficking, which is hardly a representative sample (Polaris, 2019). Moreover, this is only counting those victims who come forward and identify themselves as victims; so of this group, we're missing 96% of the data. To make matters worse, migrants, refugees, and the children of migrants and refugees are also sex trafficked at absolutely abhorrent rates, yet don't report the fact that they're being trafficked (and thus their age of entry into sex trafficking) for many of the same reasons that other vulnerable groups don't do so. Thus, even if we were to have representative samples from those who do come forward and identify themselves as victims of sex trafficking, we'd still be missing huge swaths of the affected population that we need to consider for an accurate analysis.

This all raises a very important question: what else are these crucial analyses missing?

References

- Cianciarulo, M. S. (2007). Modern-day slavery and cultural bias: proposals for reforming the U.S. visa system for victims of international human trafficking. Nevada Law Journal, Vol. 7, Issue 3 (Summer 2007), pp. 826-840

- Edwards, J., Iritani, B., & Hallfors, D. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among adolescents in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 82: pp 354-358.

- Estes, R. and Weiner, N. (2001). The commercial sexual exploitation of children in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work.

- Hall, C. (2014) Is one of the most-cited statistics about sex work wrong? The Atlantic. Retrieved September 13, 2022 from

- Har, J. (2013) Is the average age of entry into sex trafficking between 12 and 14 years old? PolitiFact. Retrieved September 13, 2022 from

- Kessler, G. (2015) The four-Pinocchio claim that ‘on average, girls first become victims of sex trafficking at 13 years old'. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 13, 2022 from

- LaCapria, K. (2020) Do 800,000 children go missing each year in the United States? Truth or Fiction. Retrieved September 13, 2022 from

- Lyon, W. (2014) Age of entry research: A compendium. Sex Work Research. Retrieved September 13, 2022 from

- Polaris. (2019a) Sex trafficking in the U.S.: A closer look at U.S. citizen victims. Polaris. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- Polaris. (2019) 2019 date report: The U.S. national human trafficking hotline. Polaris. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- Trend-Cunningham, F. J. & Jacquin, K. (2018) Age of entry into sex work is a myth. Conference: American College of Forensic Psychology.